Animal Farm

George Orwell

Few authors—indeed, few people—lend their surname to the vernacular. When you hear someone describe a governmental edict as “positively Orwellian,” it is very likely a reference to either Animal Farm or 1984, two of George Orwell’s dystopian classics. Both have implications for leadership, but especially so Animal Farm, a parable featuring various barnyard animals jockeying for power over one another.

The New Colossus

Emma Lazarus

America’s love-hate relationship with nationalistic fervor and with the immigration of anyone who came after oneself would seem to cast doubt on the sincerity of the sonnet at the base of the Statue of Liberty. At the same time, it has lit the lamp of hope for generations of people around the world who have looked to America as the guardian of liberty and of their hopes and dreams for a better life.

Emma Lazarus’s words want to pry open our closed arms to embrace people of all religions, all nationalities, all cultures, because the United States is first an idea, a land of freedom, not a home for people of this color or that religion. An excerpt of the sonnet is familiar to all:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

The Grapes of Wrath

John Steinbeck

Tom Joad, a recently paroled ex-con, assumes the mantle of leadership as his family moves from Dust Bowl poverty in Oklahoma to an uncertain, and increasingly bleak, life in California. Author John Steinbeck, commenting on the craft of writing, always insisted than a classic tale had to concern everyone, or it would not stand the test of time. Today, three generations removed from the Great Depression, and enjoying a bounty undreamed of then, people everywhere can still see themselves in the Joad family’s journey, and leaders everywhere can see themselves in Tom Joad’s leadership.

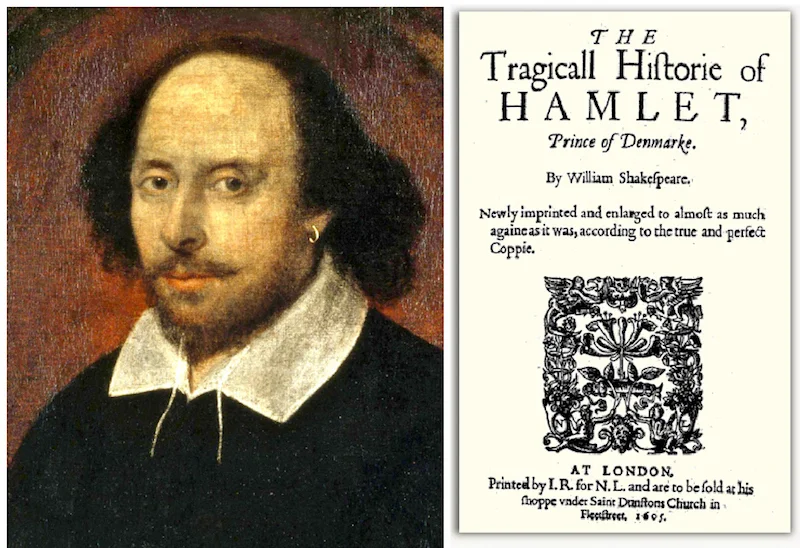

Hamlet

William Shakespeare

Some of the best lines in this 400-year-old play have practical applications for twenty-first-century leadership. For example, in Act I, the laughable character Polonius offers some sage advice to Hamlet:

“This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

Clearly, one of the big problems facing many leaders is the difficulty of arriving at truth and believing it. Everyone lies to himself or herself. For most people it is a moral failing with only modest implications. But for leaders, whose truth affects the lives and fortunes of many others, lying to oneself can be a big problem. It’s one thing to look in a mirror and tell yourself you’re the prettiest person in the universe. It’s quite another to tell yourself that you have all the answers or that your judgment is better than anyone else’s.

Ask yourself: What lies do you tell yourself? Why? What truth are you refusing to acknowledge? What half-truths or untruths do you perpetuate?

Here’s another example. In Act I, Polonius counsels his son Laertes, who is embarking for Paris:

“Give every man thine ear, but few thy voice;

Take each man’s censure, but reserve thy judgment.”

In other words, listen more than you talk, and think before you speak. If someone speaks ill of you, accept it with equanimity. This, too, is good counsel for us all. Alas, most of us are like Polonius; we would rather dish out advice to others than take it for ourselves.

Here’s one more. In the same passage, Polonius offers more time-tested counsel:

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be,

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.”

This recommendation is well-taken for everyone, too, and it is doubly true for leaders, who need to set a virtuous example. Obviously there are times when borrowing is sensible—home mortgages, student loans, start-up capital—but wanton borrowing to cover routine expenses is a perilous course, from which it can be difficult to disentangle oneself.

Julius Caesar

William Shakespeare

Classics scholar Garry Wills has observed that Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar is extraordinary because it has no villains. “Although each leading character has his own self-interest in mind, his own pride (which he thinks of as honor), he also believes he is acting for Rome and its fortunes,” Wills wrote. “Rome eats at them, and they eat at Rome, bringing it down in the name of its own greatness.” Is this not the fate of so many great companies?

King Lear

William Shakespeare

Perhaps the greatest tragedy in English literature, King Lear tells the story of a monarch who wishes to retire. He announces he will divide his estate unequally among his three daughters—Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia—with the largest share going to the daughter who loves him the most. For a modern treatment of the centuries-old story, see A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley.

The Leader

Eugène Ionesco

Ionesco (pronounced ee-uh-NESS-coh) was an existential 20th Century playwright who questioned the banalities and orthodoxies of his time. His short play The Leader is paradigmatic. Like all Theater of the Absurd works, The Leader has a bizarre and symbolic plot. A small group of persons await the arrival of “The Leader,” who, when he finally arrives, is without a head. Nevertheless, he is heralded as a genius, and the onlookers, depersonalized and nameless, are thrilled to have seen him.

Lord of the Flies

William Golding

This popular novel, which has become required reading in many high-school literature classes, explores the nature of small-group dynamics and natural leadership. The use of a conch to summon people is a metaphor for communication that brings a common focus to a crowd, and thereby facilitates leadership.

To a Louse, On Seeing One on a Lady’s Bonnet at Church

Robert Burns

The final verse of this 1786 Scottish poem is a reminder to all, and especially to leaders, that we can never know how others view and regard us. It is, in a sense, a plea for empathy.

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

It wad frae mony a blunder free us,

An’ foolish notion:

What airs in dress an’ gait wad lea’e us,

An’ ev’n devotion!

In today’s vernacular, the first two lines can be read as:

Wish for the power the good Lord give us

To see ourselves as others must see us!

One of my high-school English teachers gave me a copy of this poem a few days before I graduated as a reminder to check my willfulness and arrogance prior to heading off to college. It was a little act of leadership for which I have always been grateful.

Mother to Son

Langston Hughes

This lyrical poem poignantly expresses the basic challenges that millions of people face every day. In a few words, a mother inspires her son to a life of industry and integrity. Langston Hughes wrote:

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

Sublime.

O Captain! My Captain!

Walt Whitman

This metaphoric poem, an elegy to Abraham Lincoln, was written just weeks after his assassination while the nation mourned. The poem captures the intensity of devotion people may feel to a leader, especially one who has touched their hearts and is then taken from them. (The poem makes a cameo appearance a century later in the film Dead Poets Society, when the teacher John Keating, portrayed by Robin Williams, invites his students to call him “Oh captain, my captain” if they so wish.)

Pillars of the Earth

Ken Follett

This is a rip-roaring historical thriller set in medieval England, and it has profound lessons on leadership. Be forewarned: Pillars is long, 973 pages to be precise. But it stakes a claim on your mind and doesn’t let go. Ken Follett knows how to transport a reader to a different time and place, and he does it magnificently here. Trust me, once you begin Pillars, you won’t put it down.

Rhinocéros

Eugène Ionesco

Ionesco, an absurdist playwright, often used a character by the name of Bérenger as an observer and narrator to represent himself. In Rhinocéros, Bérenger watches in disbelief as, one by one, his friends morph into rhinoceroses. Bérenger eventually stands alone. The play is understood to be a statement of protest against dehumanizing ideologies that demand conformity, which Ionesco witnessed as fascists gained control in his native Romania in the 1930s. Today Rhinocéros is a reminder to think for oneself and especially to question what everyone else is taking for granted.

The Road Not Taken

Robert Frost

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,” Robert Frost wrote in 1920, “And sorry I could not travel both, And be one traveler, long I stood.” This simple poem of four stanzas, just twenty lines, offers a visual feast to illustrate the dilemma of two attractive choices. I count hiking in the woods as one of my favorite pastimes. Frost’s poem is never far from my mind on the trails, especially in the autumn when the hickory, beech, and maple trees at one of my favorite forks in the Daniel Wright Woods, near Lake Forest, Illinois, turn brilliantly yellow.

The Stranger

Albert Camus

One of the great existential novels of the 20th century, The Stranger brings home the belief that we are all, individually, responsible for our own life. The novel’s central character, Meursault, is so stoical he feels no emotion at his own mother’s funeral. Later, he kills a man and, after being convicted of the crime, is sentenced to death. Camus (pronounced kah-MOO) offers big lessons in the consequences, on oneself and on others, of such a cold and impersonal presence in the world.

Then We Came to the End: A Novel

Joshua Ferris

Anyone who has ever populated an office of cubicles and worked under the threat of an imminent layoff will resonate to this novel. I’d love to see it as a movie.

To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee

A modern classic, Mockingbird addresses racial tension in a warm and tenderhearted way. Its hero, Atticus Finch, a single father and small-town attorney in Alabama, has become a fictional icon for lawyers ever since the book’s publication in 1960. His daughter, Scout, is thought to be the author herself, and her friend Dill is believed to be based on Truman Capote, who as a child spent summers with his aunt next door to Lee’s home. Lee and Capote became close friends into adulthood.

Waiting for Godot

Samuel Beckett

The point of this absurdist play is often unclear to people who view it, and that, it seems to me, is the cornerstone of its message for leaders: The why is of equal if not greater importance than the what or the who. People have a basic need to understand their situation, and in the absence of understanding they cannot do anything about it. All too often, leaders, especially in business, assume but do not explain the why. That’s a big mistake.