LEADERSHIP DOCUMENTS

Here is an annotated list of famous historical examples of documents for leadership. These are declarations of belief or policy, each of which had an outsize impact on the organization or culture for which or by which it was set forth.

We have striven for a diverse array of statements, from both world history and contemporary society, and from both governmental institutions and independent entities. Some of these statements have determined the course of history, while others have affected only a few thousand people. In every instance, writing and publishing the document was instrumental; had its authors or sponsors remained silent, their leadership would never have come into being.

The Arthashastra

Kautilya (also known as Chanakya and Vishnugupta)

350 BCE

Written in ancient India, and not unlike The Prince of nearly two millennia later, The Arthashastra is a manual for rulers. The title, in Sanskrit, is variously translated as the “science” of political economics or of good governance. Its putative author, Kautilya (350-283 BC), was a scholar at Takshashila and an advisor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya (340-293 BCE), who established the Mauryan Empire and expanded it across the subcontinent. He was also something of a kingmaker, inasmuch as he masterminded Chandragupta’s ascendancy to power.

While The Arthashastra covers a wide gamut of affairs—everything from statecraft and economics to espionage and assassination to day-to-day scheduling of business—its emphasis and its main value for us today lies in its treatment of propaganda. Among the particular tactics it addresses are epithets, exaggeration, extrapolation, false flags, generalities, and transference.

The manual was lost for hundreds of years. Palm leaves inscribed with its text were discovered in 1904.

The Bill of Rights

Parliament of England

1689

A century before the United States Constitution codified rights for the new American republic, England’s Parliament adopted constraints on the monarchy. The Bill of Rights of 1689 established regular elections and freedom of speech for Parliament, and it enshrined the right to petition the throne without fear of retribution, all concepts articulated by England’s foremost enlightenment thinker, John Locke.

Bill of Rights to the United States Constitution

James Madison

1789

Two years after Congress had laid the foundation of the new government, a major obstacle remained. The Constitution had articulated how the government would look and work, but in significant respects it fell short of protecting people from tyranny. One large political faction, the Anti-Federalists, refused to move forward without such protections. The answer lay in the articulation of core rights, most notably religion, speech and press, assembly, and petition. Together with other rights set forth in the first ten amendments, they constitute the Bill of Rights.

Burning Man Principles

Larry Harvey

2004

I have never understood the appeal of an arts festival in the sweltering summer heat of a Nevada desert, but maybe I’m just an old stuffed snot. I do resonate, however, to the principles articulated for the annual Burning Man Festival by co-founder Larry Harvey. Essentially a statement of values, they’re intended to describe rather than prescribe “the community’s ethos and culture as it had organically developed since the event’s inception” in 2001.

To-wit:

Radical Inclusion

Anyone may be a part of Burning Man. We welcome and respect the stranger. No prerequisites exist for participation in our community.

Gifting

Burning Man is devoted to acts of gift giving. The value of a gift is unconditional. Gifting does not contemplate a return or an exchange for something of equal value.

“Corpus” by michael christian, berkeley, california (2019)

Decommodification

In order to preserve the spirit of gifting, our community seeks to create social environments that are unmediated by commercial sponsorships, transactions, or advertising. We stand ready to protect our culture from such exploitation. We resist the substitution of consumption for participatory experience.

Radical Self-Reliance

Burning Man encourages the individual to discover, exercise and rely on his or her inner resources.

Radical Self-Expression

Radical self-expression arises from the unique gifts of the individual. No one other than the individual or a collaborating group can determine its content. It is offered as a gift to others. In this spirit, the giver should respect the rights and liberties of the recipient.

Communal Effort

Our community values creative cooperation and collaboration. We strive to produce, promote and protect social networks, public spaces, works of art, and methods of communication that support such interaction.

Civic Responsibility

We value civil society. Community members who organize events should assume responsibility for public welfare and endeavor to communicate civic responsibilities to participants. They must also assume responsibility for conducting events in accordance with local, state and federal laws.

Leaving No Trace

Our community respects the environment. We are committed to leaving no physical trace of our activities wherever we gather. We clean up after ourselves and endeavor, whenever possible, to leave such places in a better state than when we found them.

Participation

Our community is committed to a radically participatory ethic. We believe that transformative change, whether in the individual or in society, can occur only through the medium of deeply personal participation. We achieve being through doing. Everyone is invited to work. Everyone is invited to play. We make the world real through actions that open the heart.

Immediacy

Immediate experience is, in many ways, the most important touchstone of value in our culture. We seek to overcome barriers that stand between us and a recognition of our inner selves, the reality of those around us, participation in society, and contact with a natural world exceeding human powers. No idea can substitute for this experience.

Cadet Honor Code

United States Military Academy (West Point)

1802

West Point’s honor code is simple and straightforward: “A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do.” Though accompanied by an enforcement process and a set of straightforward definitions, the Code itself could not be simpler or clearer. A corollary of the Code has to do with an officer’s response to an illegal order; cadets are taught they not only have the right to ignore it, they have the obligation to ignore it.

The Cluetrain Manifesto

Rick Levine, Christopher Locke, Doc Searls, David Weinberger

1999

What began as a Web site (cluetrain.com) evolved into a set of ninety-five prescient observations and convictions about the impact of the Internet on business. From what I can see, most companies have looked the other way. They shouldn’t. My favorite is No. 20: “Companies need to realize their markets are often laughing. At them.”

Common Sense

Thomas Paine

1776

This little pamphlet—more than any other document, including the Declaration of Independence itself—aroused popular sentiment of colonial Americans against Great Britain. On its publication it was an immediate sensation. People read it everywhere. With simple, even crude, declarative sentences, it made the case for independence. The pamphlet argued it was simple “common sense” that an island cannot for long control a continent thousands of miles distant.

The 38-year-old Paine was a recent British émigré who had lived in the colonies only two years. At the time he wrote the pamphlet, few colonists were thinking in terms of independence from England. Common Sense changed that. To be sure, it helped that its publication coincided with a speech to Parliament by George III in which the king denounced the colonists as traitors and threatened to send mercenaries to put down the rebellion.

General George Washington, whose army was surrounded by the British, ordered his officers to read the incendiary pamphlet to all soldiers. It is no exaggeration to say Common Sense—”slapdash as it is, rambling as it is, crude as it is,” in the words of the eminent Harvard historian Bernard Bailyn—changed the course of history. Words can do that.

The Communist Manifesto

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

1848

The authors of this short polemic could not possibly know the havoc they were unleashing with their essay. Although a few of its principles, such as banning child labor, enjoy broad support today in the Western world, most, such as centralizing authority and dispersing people from cities to the countryside, are so extreme as to be dystopian.

Contract With America

Representatives Newt Gingrich and Richard Armey

1994

Building on President Ronald Reagan’s State of the Union Address of 1985 and Sen. Barry M. Goldwater’s acceptance speech of the Republican presidential nomination in 1964—in which Goldwater declared that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice”—Newt Gingrich and Richard Armey published a list of eight reforms and ten bills that a Republican-controlled Congress would enact. Six weeks later Americans elected GOP majorities in both the House and Senate for the first time in a generation. Some of the reforms and measures were enacted, while others were defeated or were vetoed by President Bill Clinton.

Declaration of Independence of the United States of America

Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams

1776

More than announcing the formation of a new nation, the Declaration of Independence explained why it was necessary and what it would mean. It listed the grievances against King George III of England, and it proclaimed that all men were created inherently equal. This notion, the work of the Enlightenment thinkers Rousseau and Montesquieu, is enshrined in the Declaration’s second sentence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” America could not begin to live up to that ideal for two more centuries, and even today it is unfinished business.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen

National Constituent Assembly of France

1789

This document, the culmination of a century of thinking by the likes of Rousseau and Montesquieu, established human rights that most of the Western world takes for granted today (if forever quarreling over their application). Adopted at the same time the United States Congress was deliberating over the Bill of Rights, and later amended to add an emphasis on equality, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen is one of history’s greatest documents.

Declaration of Rights and Sentiments

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

1848

Patterned after the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and indeed using much of the same language, the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments was the first articulation of women’s suffrage. Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote it for the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, which approved it after a lengthy debate. What it lacks in creativity it more than makes up in boldness. Of note, the call for suffrage met significant opposition at the Seneca Falls conclave even among women. It was Frederick Douglass, in attendance at the convention, who argued most eloquently for it.

Ecclesiastes 3

Attributed to King Solomon

n.d.

Familiar to all, this is the litany of “To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven”:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, a time to reap that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.”

Pete Seeger used the verse for the lyrics to his popular song “Turn! Turn! Turn!” recorded by various singers from the 1960s on. Note the reliance in the verse on the rhetorical device of internal repetition: “A time to . . . a time to . . .”

Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln

1862

Officially issued on January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation invoked President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime powers to free more than three million enslaved people held in the ten rebellious states of the Confederacy.

However, because it was a wartime edict not passed by the Congress, its effect would end upon the cessation of hostilities with the Confederacy, thereby necessitating the 13th Amendment to ensure the permanent freedom of all enslaved peoples.

As a strategic measure, the Emancipation officially proclaimed ending slavery as a purpose of the Union’s cause. Later in 1863, at the dedication ceremony at Gettysburg, the president would refer indirectly to the newfound purpose as “a new birth of freedom.”

The Federalist

Publius (Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison)

1787-1788

Responding to Anti-Federalist criticism of the proposed Constitution, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, later to be joined by James Madison, began writing a series of essays in its behalf and publishing them under the pseudonym Publius in a pair of New York newspapers. The essays were pivotal in building support for the federal system.

Golden Rule

n.d.

Variously worded but conceptually consistent, this basic precept is foundational to virtually every religion around the world and throughout history. (If only people would honor it!)

Baha’i: “Lay not on any soul a load that you would not wish laid upon you, and desire not for anyone the things you would not desire for yourself.”

Buddhism: “Treat not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.” (Buddha)

Christianity: “In everything, do to others as you would have them do to you, for this is the law of the prophets.” (Jesus)

Confucianism: “One word which sums up the basis for all good conduct: loving-kindness. Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.” (Confucius)

Hinduism: “This is the sum of duty: Do not do to others what would cause pain if done to you.”

Islam: “Not one of you truly believes until you wish for others what you wish for yourself.” (Mohammed)

Jainism: “One should treat all creatures in the world as one would like to be treated.”

Judaism: “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole Torah; all the rest is commentary. Go learn it.” (Hillel the Elder)

Sikhism: “I am a stranger to no one, and no one is a stranger to me. Indeed, I am a friend to all.”

Taoism: “Regard your neighbor’s gain as your own gain and your neighbor’s loss as your own loss.”

Zoroastrianism: “Do not do unto others whatever is injurious to yourself.”

Hammurabi’s Code (also known as Codex Hammurabi and the Code of Hammurabi)

1754 BCE

Arguably the world’s oldest codification of law, Hammurabi’s Code consists of two hundred forty-eight edicts handed down by Hammurabi (say it ah-mer-RAH-bee), the first king of the Babylonian Empire in Mesopotamia more than a millennium before civilization arose in Greece.

Archaeologists unearthed a long-lost copy in 1901 on a six-foot stele, or stone tablet (from which the phrase “written in stone” derives). It now awes tourists from its pedestal in the Louvre. So great was its force that it ensured peace across Babylon.

Among other things, the Code’s edicts enshrined the king with divinely endowed authority but also recognized that rulers have special moral obligations, in particular the responsibility to promote righteousness, combat evil, and fear God. They also set forth definitions, standards, protocols, and requirements for compliance with various civil, criminal, and contractual laws. Punishment, as in many ancient cultures, was draconian.

For us, so many centuries later, Hammurabi’s Code serves as a reminder that leaders and the led share obligations to comply with the law and that leaders must constantly demonstrate their fealty to the law and their commitment to the common weal.

Jemez Principles of Democratic Organizing

Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice

Jemez, New Mexico

1996

More than twenty years after their adoption, the Jemez Principles (Jemez is pronounced HAY-mess) are finally beginning to find a warm embrace in liberal and progressive social and environmental organizations. They set a high standard for democratic organizers, to wit:

1. Be Inclusive

If we hope to achieve just societies that include all people in decision-making and assure that all people have an equitable share of the wealth and the work of this world, then we must work to build that kind of inclusiveness into our own movement in order to develop alternative policies and institutions to the treaties policies under neo- liberalism.

This requires more than tokenism, it cannot be achieved without diversity at the planning table, in staffing, and in coordination. It may delay achievement of other important goals, it will require discussion, hard work, patience, and advance planning. It may involve conflict, but through this conflict, we can learn better ways of working together. It’s about building alternative institutions, movement building, and not compromising out in order to be accepted into the anti-globalization club.

2. Emphasis on Bottom-Up Organizing

To succeed, it is important to reach out into new constituencies, and to reach within all levels of leadership and membership base of the organizations that are already involved in our networks. We must be continually building and strengthening a base which provides our credibility, our strategies, mobilizations, leadership development, and the energy for the work we must do daily.

3. Let People Speak for Themselves

We must be sure that relevant voices of people directly affected are heard. Ways must be provided for spokespersons to represent and be responsible to the affected constituencies. It is important for organizations to clarify their roles, and who they represent, and to assure accountability within our structures.

4. Work Together In Solidarity and Mutuality

Groups working on similar issues with compatible visions should consciously act in solidarity, mutuality and support each other’s work. In the long run, a more significant step is to incorporate the goals and values of other groups with your own work, in order to build strong relationships. For instance, in the long run, it is more important that labor unions and community economic development projects include the issue of environmental sustainability in their own strategies, rather than just lending support to the environmental organizations. So communications, strategies and resource sharing is critical, to help us see our connections and build on these.

5. Build Just Relationships Among Ourselves

We need to treat each other with justice and respect, both on an individual and an organizational level, in this country and across borders. Defining and developing “just relationships” will be a process that won’t happen overnight. It must include clarity about decision-making, sharing strategies, and resource distribution. There are clearly many skills necessary to succeed, and we need to determine the ways for those with different skills to coordinate and be accountable to one another.

6. Commitment to Self-Transformation

As we change societies, we must change from operating on the mode of individualism to community-centeredness. We must “walk our talk.” We must be the values that we say we’re struggling for and we must be justice, be peace, be community.

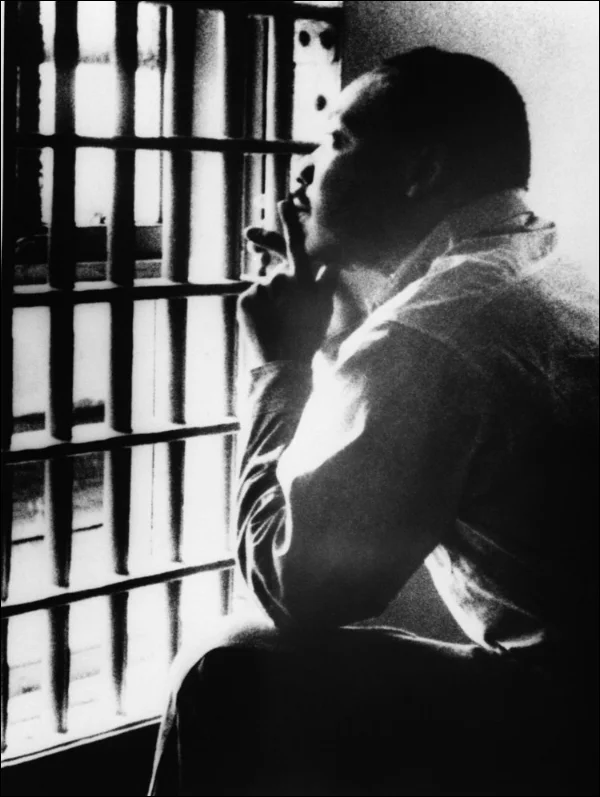

Letter From a Birmingham Jail

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

1963

Now studied in college literature classes worldwide, King’s eloquent letter appealed to white clergymen who had criticized the civil rights movement as unnecessary and premature— premature, they said, nearly a century after the Thirteenth Amendment! It brings to mind Hillel the Elder's well-known aphorism: “If not now, when?"

In the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, King wrote: "I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say ‘wait.' But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society . . . ; when your first name becomes ‘nigger’ and your middle name becomes ‘boy’ (however old you are) and your last name becomes ‘John,’ and when your wife and mother are never given the respected title ‘Mrs.’; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of ‘nobodyness’—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.”

Letters to Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway

Warren Buffet

1966 to Present

Ever since taking control of a small textile company in 1965, Warren Buffet has been showing the world how to invest, how to manage, how to lead, and how to communicate with key stakeholders. He has done a masterful job at all four. In particular, his annual letters to investors are a thing of beauty. They are enterprising, engaging, energizing, elevating, and ennobling, and they are even well-written. Best of all they are refreshingly humble and candid.

For example, in his 2018 letter looking back on 2017, a year when Berkshire Hathaway's value grew by $65 billion, Buffet wrote: "A large portion of our gain did not come from anything we accomplished at Berkshire." Rather, it was the tax legislation he so adamantly opposed that contributed $29 billion to Berkshire's valuation. You can read the letters at http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/letters.html or in digital or paperback format from Amazon at http://www.amazon.com/BerkshireHathaway-Letters-Shareholders-Buffett/dp/1595910778.

Letter to Share Owners of General Electric

1992

Jack Welch

If you can find an extant copy of General Electric’s 1992 annual report, get hold of it and keep it. Jack Welch, the company’s legendary CEO, used his annual letter that year to describe a matrix of four types of business leaders.

Type I leaders “deliver on commitments, financial or otherwise, and share our values,” Welch wrote. They are the stars, the keepers. Type II leaders do neither and must be shown the exit. That much is easy. The real difficulty lies with Type III and Type IV. Type III leaders embrace the values but have missed their commitments. Welch advocated giving them a second and even a third chance in other assignments. Type IV leaders, who make their commitments but neglect or trample over the values, must be exited in spite of their good numbers.

A summary of the matrix appears in Jack Welch Speaks: Wit and Wisdom from the World’s Greatest Business Leader by Janet Lowe (Wiley, 2008, pp. 108-111).

Magna Carta

The Barons of King John of England

1215

More symbol than statute, the Magna Carta never carried the force that people now suppose, and most of it was eventually repealed. However, it laid the groundwork for the concept of rule by law, and it inspired important subsequent edicts and declarations, including the Rights of Man in France and the Bill of Rights in the United States.

Signing the Mayflower Compact 1620 (Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, c. 1899)

Mayflower Compact

William Bradford

1620

The Mayflower Compact was an early social contract establishing a simple system of governance. It was necessary because the Mayflower had landed hundreds of miles off course, and some of its passengers were contending that its mission was therefore moot.

Signatories to the compact declared they “covenant and combine [themselves] together into a civil body politic; for [their] better ordering, and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony; unto which [they] promise all due submission and obedience.”

As a historical note, the validity of the commitments to the Compact is disputable, as Bradford had ordered the ship to remain at anchor in Provincetown Harbor off Cape Cod until the document was signed, and therefore the signatures can perhaps be regarded as under duress.

Mein Kampf

Adolph Hitler

1923-1925

Still controversial and extremely offensive, and outright illegal in parts of the world, Mein Kampf is studied today as a declaration of political polemic, propaganda, and intent, though it stopped well short of detailing the depths of depravity to which Adolph Hitler would take Germany. We include it here because of its historical significance and powerful impact on the German people.

Nicene Creed

First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea

325

This concise statement is the very definition of Christianity, and of the Trinity, in all but a few Christian denominations. Seventeen centuries after its adoption, hundreds of millions of people recite it at every worship service or rite.

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences

Martin Luther

1517

The initial impetus of the Protestant Reformation, this document was a protest against the practice of paying, rather than praying, for divine grace. Luther nailed the Theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany. Within five years local people began turning away from Roman Catholic mass to attend new “Lutheran” services.

Nordstrom Employee Handbook

Nordstrom Inc.

For many years Nordstrom distributed a handbook to employees consisting of only a single page, measuring five by seven inches. It contained all of seventy-two words. It said only: “We are glad to have you with our Company. Our number one goal is to provide outstanding customer service. Set both your personal and professional goals high. We have great confidence in your ability to achieve them. Nordstrom Rules: Rule #1: Use best judgment in all situations. There will be no additional rules. Please feel free to ask your department manager, store manager, or division general manager any question at anytime.” The company has explained that, owing to the complexity of employment law, it can no longer rely on such a brief, simple handbook, but wants all the same to preserve an atmosphere of decentralized good judgment.

Owner’s Manual for Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway

Warren Buffet

1996

Every publicly traded company should emulate this document. Its candor, nobility, and clarity are a breath of fresh air. I especially like its simple explanation of the critical difference between book value and intrinsic value, which has long guided the selection of investments by Warren Buffet and his partner, Charlie Munger.

To illustrate the difference in everyday terms, Buffet cites the example of the economic value of a college education. Tuition represents the book value, the nominal cost and investment. The difference in lifetime earnings between a college graduate and a non-graduate is the intrinsic economic value. Plainly the full economic value of a college education is greater than the tuition, and that accounts for the wisdom of investing in it.

Port Huron Statement

Tom Hayden

1962

The Port Huron Statement was a manifesto of the student left during the 1960s. Officially the doctrine of the Students for a Democratic Society, it captured the angst and anxiety felt by many Baby Boomers. Less than twenty years had passed since the Holocaust and the dawn of the Atomic Age, and across the South institutionalized racism was under challenge. Change was in the air, but so was a pall of pessimism.

The statement took on greater importance as U.S. involvement in Vietnam grew and protests erupted on college campuses. Today, viewed from a distance of fifty years, the Port Huron Statement seems both hopelessly idealistic and sweetly iconoclastic.

Preamble to the United States Constitution

James Madison

1789

A single sentence of fifty-two words, the Preamble has a powerful brevity. Functionally it is merely an introduction to the Constitution. Substantively, it establishes the precept that the people of the United States were creating their own government, and it declared the purposes of that government as extending broadly to “the general welfare” of the populace: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” Note also its use of the first-person plural We. Two centuries later, the Preamble remains among the most important sentences ever written.

Prospectus (S-1), Google Initial Public Offering

Larry Page and Sergey Brin

2004

Google’s S-1, the statement required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission of all companies embarking on an initial public offering, is legendary both for its candor and for its boat-rocking unorthodoxy. “Google is not a conventional company,” the company declares. “We do not intend to become one. Throughout Google’s evolution as a privately held company, we have managed Google differently. We have also emphasized an atmosphere of creativity and challenge, which has helped us provide unbiased, accurate and free access to information for those who rely on us around the world.” Anyone who aspires to or exercises leadership in business should read and think carefully about the entire document.The full text of the prospectus is available at the U.S. government’s National Archives Web site: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1288776/000119312504073639/ds1.htm#toc16167_

Starbucks Green Apron Book

Starbucks Coffee Company

I have a well-worn copy of this little booklet, a splendid example of translating large goals and values to specific, everyday priorities for which any customer facing employee can take personal responsibility. Just the right size to slip into a back pocket of blue jeans, it’s an outstanding example of the formal voice. These booklets are hard to come by, but a search on eBay may turn up one or two.

Sullivan Principles

The Rev. Leon Sullivan

1977 and 1999

Conceived and issued during the nadir of South Africa’s apartheid in the 1970s, and then revised for global application in the 1990s, the Sullivan Principles are two codes of conduct for corporations striving to do right in morally obtuse situations. Both documents were the impetus of the Rev. Leon Sullivan of South Africa.

The initial document was intended to apply international economic pressure on South Africa as a protest of apartheid. After a few years, the Sullivan Principles became part and parcel of American and European corporate presence in South Africa.

The original Sullivan Principles read:

Non-segregation of the races in all eating, comfort, and work facilities.

Equal and fair employment practices for all employees.

Equal pay for all employees doing equal or comparable work for the same period of time.

Initiation of and development of training programs that will prepare, in substantial numbers, blacks and other nonwhites for supervisory, administrative, clerical, and technical jobs.

Increasing the number of blacks and other nonwhites in management and supervisory positions.

Improving the quality of life for blacks and other nonwhites outside the work environment in such areas as housing, transportation, school, recreation, and health facilities.

Working to eliminate laws and customs that impede social, economic, and political justice. (added in 1984)

The global Sullivan Principles went beyond the original focus to include the advancement of human rights and social justice worldwide. The revised Sullivan Principles read:

As a company which endorses the Global Sullivan Principles we will respect the law, and as a responsible member of society we will apply these Principles with integrity consistent with the legitimate role of business. We will develop and implement company policies, procedures, training and internal reporting structures to ensure commitment to these principles throughout our organisation. We believe the application of these Principles will achieve greater tolerance and better understanding among peoples, and advance the culture of peace.

Accordingly, we will:

Express our support for universal human rights and, particularly, those of our employees, the communities within which we operate, and parties with whom we do business.

Promote equal opportunity for our employees at all levels of the company with respect to issues such as color, race, gender, age, ethnicity or religious beliefs, and operate without unacceptable worker treatment such as the exploitation of children, physical punishment, female abuse, involuntary servitude, or other forms of abuse.

Respect our employees' voluntary freedom of association.

Compensate our employees to enable them to meet at least their basic needs and provide the opportunity to improve their skill and capability to raise their social and economic opportunities.

Provide a safe and healthy workplace; protect human health and the environment; and promote sustainable development.

Promote fair competition including respect for intellectual and other property rights, and not offer, pay or accept bribes.

Work with governments and communities in which we do business to improve the quality of life in those communities – their educational, cultural, economic and social well-being – and seek to provide training and opportunities for workers from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Promote the application of these principles by those with whom we do business.

We will be transparent in our implementation of these principles and provide information which demonstrates publicly our commitment to them.

Why Women Should Vote

Jane Addams

1915

This pamphlet explained to men and women alike why women should assume a broader civic role. It stopped well short of challenging the traditional authority of men, but it urged women to become involved in schools and public health and welfare. Addams, the Chicago-based social worker, would win the Nobel Prize in 1931.

Famous Historic Examples of the Formal Voice:

Noteworthy Speeches, Lectures, Sermons, and Debates

Rockefeller Chapel, The University of Chicago

Aims of Education

The University of Chicago

The first lecture every new University of Chicago undergraduate attends is the annual Aims of Education address, given by a senior member of the faculty to the incoming class in Rockefeller Chapel every September since 1963. The lecture is given on the Sunday afternoon preceding a week of orientation; parents attend as well, and afterward the students have their class picture taken while the parents adjourn for cocktails.

The lecture gives high purpose to the grueling education these students will experience. (It isn’t unusual for UChicago undergraduates to be assigned hundreds of pages of reading a night. The Aims of Education address explains why they are to be subjected to such a torturous but rewarding experience.) You can access recent lectures here: http://aims.uchicago.edu/page/past-speakers.

“Ain’t I a Woman?”

Sojourner Truth

1851

This is the legendary speech to the Women’s Convention of Akron, Ohio for which Sojourner Truth is remembered.

Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about? That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

A few sentences later, she declared she was done, and she sat down. She had made her point and then some.

The American Promise

Lyndon B. Johnson

1965

A week after the march on Selma, Alabama, President Lyndon B. Johnson went before a joint session of Congress to present his case for passage of the Voting Rights Act. He declared he was there to speak “for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy.” Then he implored Congress to do the right thing: “There is no moral issue. It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of States rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights. I have not the slightest doubt what will be your answer.”

Apologia

Plato

399 BC

There are times when the most eloquent of words are not sufficient, and this was one of them. As recalled by Plato, Socrates, far from atoning for the offense of educating the young, declared to the Athens jury: “The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways: I to die, and you to live. Which is better God only knows.” Adjudged guilty, Socrates was sentenced to die by drinking a cup of hemlock.

Banaras Hindu University Dedication

Mohandas K. Gandhi

1916

In the midst of World War I, Mohandas K. Gandhi was asked to speak at the dedication ceremony of a new Hindu university. Until then the Indian independence movement was all but inert, for Indians were culturally imitating British ways and manners. Gandhi, adorned in a mere cloth, outraged his well-dressed audience when he declared: “There is no salvation for India unless you strip yourselves of this jewelry and hold it in trust for your country men.” The speech fundamentally shifted the debate and set the stage for Indian independence, and Gandhi became the movement’s inspirational leader.

Abraham Lincoln (Mathew Brady) in New York City, 27 February 1860

Cooper Union Address

Abraham Lincoln

27 February 1860

A declared candidate for his party’s presidential nomination, Abraham Lincoln accepted a speaking invitation at the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher’s church in Brooklyn. Word spread that the prairie lawyer, remembered for his widely publicized debates on slavery two years earlier with Sen. Stephen Douglas, was coming to town. Excitement grew, and larger quarters had to be found, so the speech was moved to the newly built Cooper Union Institute in Manhattan.

Lincoln worked for months on this speech. Contemporary accounts indicate that sophisticated Easterners, startled by the ill-kempt appearance of the awkwardly tall man, initially felt sorry for him. But when he began speaking, they were quickly enraptured.

The speech demonstrates just how powerfully an extraordinary address can establish a leader’s credibility and connection with people, and it exemplifies the particular appeal of noble purpose. The peroration is especially eloquent: "Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it." The full text of the speech is available on many Web sites, including Abraham Lincoln Online: http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/cooper.htm.

Debate on the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution

Schuyler Colfax, George Pendleton, Thaddeus Stevens, Charles Sumner, Lyman Trumbull, et al.

Congress of the United States

1865

This debate, which President Abraham Lincoln insisted on in January 1865 despite the better chances for passage in a new Congress two months later, is the subject of the Steven Spielberg movie Lincoln and of the final two chapters of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s best-seller Team of Rivals. The debate reflected three critical fault lines that would long captivate American politics: racialism, sectionalism, and federalism. Lincoln’s sense of urgency is itself an object lesson for leaders: Bless the important with immediacy.

Debate on the Compromise of 1850

John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, Jefferson Davis, Stephen A Douglas, Daniel Webster, et al.

Congress of the United States

For decades in the early nineteenth century three men dominated the U.S. Senate. Together they were known as the Great Triumvirate, the nomenclature borrowed from Roman antiquity: Henry Clay, a Whig from Kentucky; Daniel Webster, a Whig from Massachusetts; and John C. Calhoun, a Democratic apologist for slavery from South Carolina. All three would die within two years of the Compromise of 1850. Their debate, joined by Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, is among the greatest in the Senate’s long history. America’s Great Compromise by Fergus Bordewich is a colorful, well-written history of the debate, and it is an enjoyable and engaging read, as well.

Statues of Abraham lincoln and stephen douglas in the town square of ottawa, illinois

Debates, Campaign for the U.S. Senate from Illinois

Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln

1858

These seven well-publicized debates between Sen. Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, and his Republican challenger, Abraham Lincoln, were noteworthy both for their forensic elegance and for the gravity of their focus on slavery and equality.

The context was a forthcoming election that would determine which man would represent Illinois in the United States Senate. Each debate was three hours in length; crowds stood the entire time. (The first candidate had sixty minutes, his rival had ninety, and the first had thirty more as a rejoinder.) The initial debate took place in Ottawa, Illinois, about 90 miles west of Chicago; others were held in Freeport, Jonesboro, Charleston, Galesburg, Quincy, and Alton (oddly, not Chicago). Newspapers far and wide sent stenographers to record the debates and then published lengthy accounts; readers as far away as New York City followed the debates closely. The extant written record of the debates is heavily edited, both by partisan newspapers and by Lincoln, who published an edited transcript as reported by newspapers.

At the time, prior to adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment providing for direct election of the U.S. Senate, state legislatures commonly appointed U.S. senators, and so Lincoln and Douglas were campaigning for their own parties to control the Illinois legislature. Democrats won after a former Whig, who was expected to endorse Lincoln, instead threw his support to Douglas in perhaps the first October Surprise, and Douglas was subsequently re-appointed. But the circuit-riding lawyer from Springfield won his own victory: fame and respect sufficient to garner the Republican Party’s presidential nomination two years later. Without doubt the verdict of history affirms that moral victory.

Farewell Address

Dwight D. Eisenhower

17 January 1961

Edited text of Eisenhower's farewell address

Just three days before he left office, President Eisenhower requested national television time to address the American people. What many anticipated to be a merely social farewell turned out to have lasting import.

Written with his brother Milton, the speech went through twenty-one drafts, and it contained two powerful warnings. By far the better known of the two was its coinage of the term "military-industrial complex."

At the time U.S. defense spending accounted for two-thirds of all federal expenditures and about 10 percent of all U.S. economic activity, both figures far greater than today's. As a retiring president and, arguably more important, the general who saved Western democracy from fascism, Eisenhower had special standing to question such spending, and he did.

Pointing to the "conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry," he implored Americans to take note of its "grave implications," and he warned that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist."

The other warning, less known but equally prescient, had to do with the environment. He declared: "As we peer into society's future, we—you and I, and our government—must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow."

Funeral Oration

Pericles

430 BC

Pericles was to the city-state of Athens what George Washington is to the United States of America, and more. His eulogy for the fallen Athenian soldiers is one of the earliest chronicled speeches in history. We do not know its precise words, but, as recounted by Thucydides in The History of the Peloponnesian War, we do know of its exemplary use of rhetorical devices to make its messages memorable and repeatable.

We can also easily see its influence, more than two millennia later, on Abraham Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg. Pericles begins by praising ancestors, and so does Lincoln: “Four score and seven years ago.” Pericles humbles himself before the courageous soldiers, and so does Lincoln: “We cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground.” Pericles heralds Athenian democracy as unique in the world, and Lincoln does the same for American democracy: “a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition.” Pericles implores his listeners to emulate their fallen heroes, and so does Lincoln: “It is for us the living.” Lincoln’s own craftsmanship is exquisite, of course, but the parallels between the Pericles oration and his own appear too many and too clear to be accidental.

Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln

1863

This oration has been the subject of more forensic analysis than perhaps any other speech in history. Just 272 words, taking only a few minutes to deliver, it masterfully captures the essence of the American experiment.

One of my own special memories is visiting the Lincoln Memorial by myself, with no one else within eyesight, on an early-morning run as the sun was rising over Capitol Hill. In solitude I spent a half-hour in spiritual communion with Lincoln, and I read with deliberation and care his words carved on the wall.

Years later I learned that Lincoln went out of his way in writing this speech to avoid the use of I, the most commonly used word in the English language. Lincoln intuitively knew something that few other leaders appreciate: The first-person plural (we, us, our, ours) is the pronoun of choice for leaders who wish to unite. (See the entry above for the Funeral Oration by Pericles and the entry below for the Second Reply to Hayne by Henry Clay. It appears that Lincoln borrowed from both.)

“Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death”

Patrick Henry

1775

“Our brethren are already in the field!” Patrick Henry declared to the Virginia House of Burgesses. “Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

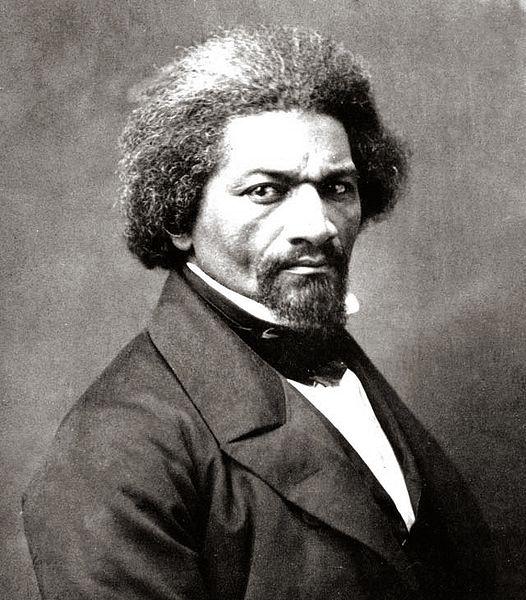

The Hypocrisy of American Slavery

Frederick Douglass

1852

Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave who bought his own freedom, accepted an invitation to speak to a Fourth of July celebration in upstate New York. He opened his remarks by noting the hypocrisy of the moment: He, lacking equality, was being asked to celebrate it. “Fellow citizens, pardon me, and allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today?” he said. “What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?”

Inaugural Address

Franklin D. Roosevelt

1933

Elected president in a referendum on his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt took the oath of office in March 1933 amid great uncertainty around his policies and around the country’s economic stability. The Great Depression was at its nadir. Determined to infuse optimism and confidence across the land, the new president declared: “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves.”

Inaugural Address

John F. Kennedy

1961

“Ask not what your country can do for you,” the young president intoned in a famously chiasmic invocation. “Ask what you can do for your country.” This speech, arguably the greatest oration by any American president since Abraham Lincoln, was filled with memorable, inspiring sentences and imagery. Two other sentences in particular also stand out: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty. “ And: “Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and a foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans.” Lest the generations ever forget them, these and four other sentences from the Inaugural Address are chiseled into the pink granite at John F. Kennedy’s gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery.

Inauguration Speech

Nelson Mandela

1994

Having been imprisoned for twenty-seven years, Nelson Mandela could reasonably have emerged a bitter, angry man. That he did not—that he instead gave the world a model of forgiveness—is itself a tribute to his greatness. In this, his 1994 inauguration address as president of South Africa, he put the divided nation on a path to uniting. “Today we celebrate not the victory of a party, but a victory for all the people of South Africa,” Mandela declared. “The time for the healing of the wounds has come. The moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come. The time to build is upon us.”

March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Martin Luther King Jr.

1963

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking to a crowd of perhaps 250,000 and to history, the legendary civil-rights leader declared: “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” His closing words still echo, as well: “When we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, Free at last, Great God all-mighty, We are free at last.” The full text of the speech is available at the U.S. government’s National Archives web site: http://www.archives.gov/press/exhibits/dreamspeech.pdf.

The Prayer of St. Francis of Assisi

Anonymous

1912

Notice the mysterious provenance and the twentieth century date above; in fact, there is no reason to attribute the famous prayer to the famous saint, and no reason to believe it dates back to his thirteenth century life. (Francis lived from 1182 to 1226.) According to Wikisource, the Prayer appears nowhere in the Omnibus of Sources, a comprehensive catalogue of the writing that Francis and his peers left behind. The earliest known publication of the invocation is 1912, when it was published in the French magazine La Clochette, or The Little Bell. The earliest known English publication of the Prayer was an anonymous entry in the Quaker periodical Friends’ Intelligencer in 1927.

Nevertheless, the Prayer is exquisite both in its literal meaning and its spiritual eloquence. The first of its two verses is familiar to all:

“Lord, make me an instrument of your peace; where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is discord, union; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; and where there is sadness, joy.”

The second verse continues:

“Grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled, as to console; to be understood, as to understand; to be loved, as to love; for it is in giving that we receive, it is in pardoning that we are pardoned, and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.”

The Canadian singer and songwriter Sarah McLachlan recorded the Prayer as a song on her 1997 album, Surfacing. It, too, is exquisite. Listen on her YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFkjdFgqOY4.

Remarks to the United Nations General Assembly

Chaim Herzog

1975

Chaim Herzog, the Israeli ambassador to the United Nations who would become the country’s sixth president, objected to General Assembly Resolution 3379, which equated Zionism with racism. Herzog declared: “For us, the Jewish people, this resolution is based on hatred, falsehood, and arrogance of Israel, [and it] is devoid of any moral or legal value.” In the face of such an abject rejection, the resolution gradually lost whatever authority it originally had, and it has been all but forgotten.

Rivonia Trial Speech

Nelson Mandela

1964

In this trial, which took its name from the Johannesburg suburb where the African National Congress had its headquarters, Nelson Mandela and seven others were convicted of crimes against the state and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. Mandela would serve 27 years, most of it at hard labor on an island in Cape Town Bay, before his release and subsequent election as president of South Africa. The sentence was actually less than what the defendants feared: capital punishment.

The speech lasted four hours, but it is the dramatic peroration that is universally recalled today as one of the finest moments in forensic history: “I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

As it happened, he lived almost twenty-five years after his release, and he became a revered elder in the battle against racism and oppression everywhere.

Second Inaugural Address

Abraham Lincoln

1865

Historians who disagree on everything else often agree that the Second Inaugural Address, not the Gettysburg Address, was Abraham Lincoln’s finest oration. It was here that Lincoln declared: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

In the crowd, listening with very different points of view, were two men: Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave whose eloquence was inspiring, and the well-known Shakespearean actor John Wilkes Booth, who would alter history in his own way six weeks later and then declare from the stage of Ford’s Theatre, “Sic semper tyrannis.” The modern historian Ronald C. White devoted an entire book, Lincoln's Greatest Speech, to the Second Inaugural Address; it is eminently readable. The full text of Lincoln’s speech is available here: http://www.historytools.org/sources/lincoln-second.pdf.

Second Reply to Hayne

Henry Clay

1830

Long regarded as the greatest speech in U.S. Senate history, Senator Henry Clay’s second reply to Senator Robert Y. Hayne is the stuff of legend. Clay was a Federalist and future Whig from Kentucky; Hayne was a Democrat from South Carolina and the immediate predecessor of John C. Calhoun, who with Clay and Daniel Webster would form the Great Triumvirate.

On one level, the Clay-Hayne debate focused on the merits of tariffs. On another level, the two senators were debating sectional interests and the legitimacy of nullification, the South’s insistence that a state could nullify, or cancel and ignore, any federal law it didn’t like. It was in the Second Reply that Clay first uttered the phrase “made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people,” which Abraham Lincoln would later borrow for the Gettysburg Address and recast as “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

The Sermon on the Mount and The Beatitudes

Jesus

c. 20

Found in Matthew 5-7 of the New Testament, the Sermon on the Mount is a lyrical compendium of the great moral teachings of Jesus. It has become for many Christians the behavioral norm of their religion. Less commonly known as the First Discourse of Matthew, the Sermon brings together the essential lessons of Jesus for those who would follow him.

They include the Beatitudes, a series of eight blessings for particular cohorts of people, and the Lord's Prayer. Rhetorically, the Beatitudes are noteworthy for their reliance on internal repetition (the conditional “Blessed are” and the consequential “for they” in all eight). Substantively, they focus the attention of Christians on humility, love, peacemaking, compassion, righteousness, and mercy—and away from judgment, condemnation, power, and arrogance.

Speech to a Joint Session of Congress

Franklin D. Roosevelt

1941

In a seven-minute address to Congress the day after Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt described December 7, 1941, as “a date which will live in infamy.” Congress responded within an hour with a declaration of war. Roosevelt spurned the advice of his secretary of state, Cordell Hull, to explain the casus belli against Japan in lengthy detail. Less is more, Roosevelt believed, and he was right.

“Tear Down This Wall”

Ronald Reagan

1987

Taking advantage of Berlin’s 750th anniversary to visit the isolated and divided city, President Reagan delivered an aggressive speech at the Berlin Wall in which he implored Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

The phrase was a flashpoint of intense disagreement within the White House. Senior aides, including Howard Baker and Colin Powell, warned it was unpresidential and potentially alienating to Gorbachev, with whom Reagan had painstakingly built a good relationship. Reagan insisted on keeping the words in the speech. The Berlin Wall would come down less than three years later.

On a personal note, I remember as a newspaper reporter attending a presidential press conference in Chicago at which another reporter asked Reagan if tearing down the Berlin Wall was even remotely realistic. It struck me as so unrealistic that I privately ridiculed the reporter's question. Years later I saw the truth: History is made of the unrealistic becoming realistic—and real.

Three Speeches to the House of Commons

Winston Churchill

1940

Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered three historic addresses to the House of Commons during the Battle of France in May and June, 1940. In the first, on May 13, only three days after Churchill succeeded Neville Chamberlain, he declared: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” In the peroration of the second, on June 4, Churchill intoned: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” In the third, on June 18, he called on Britons to rise up against a likely assault by Nazi Germany: “Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

These three speeches are commonly regarded of a piece, although a fourth speech on August 20 included another quotation of Churchillian eloquence: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,” referring to courageous Royal Air Force pilots.

Women’s Rights to the Suffrage

Susan B. Anthony

1873

Having been fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election, Susan B. Anthony embarked on a cross-country lecture tour to campaign for women’s suffrage. “It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union,” she declared. “And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government: the ballot.” She never paid the fine.