LEADERSHIP THEMES AND STORIES

IN MOVIES AND DRAMA AND ON TELEVISION

Here is an annotated bibliography of movies, drama, and television shows with compelling or important information and messages of interest to leaders.

Comments in the first person reflect the experience and judgment of Thomas Lee.

Thomas has used movies marked by an asterisk* in graduate-school classes to illustrate certain concepts in leadership for students who have limited experience of their own. For some of these movies he has included discussion questions and prompts, which you may wish to use on your own.

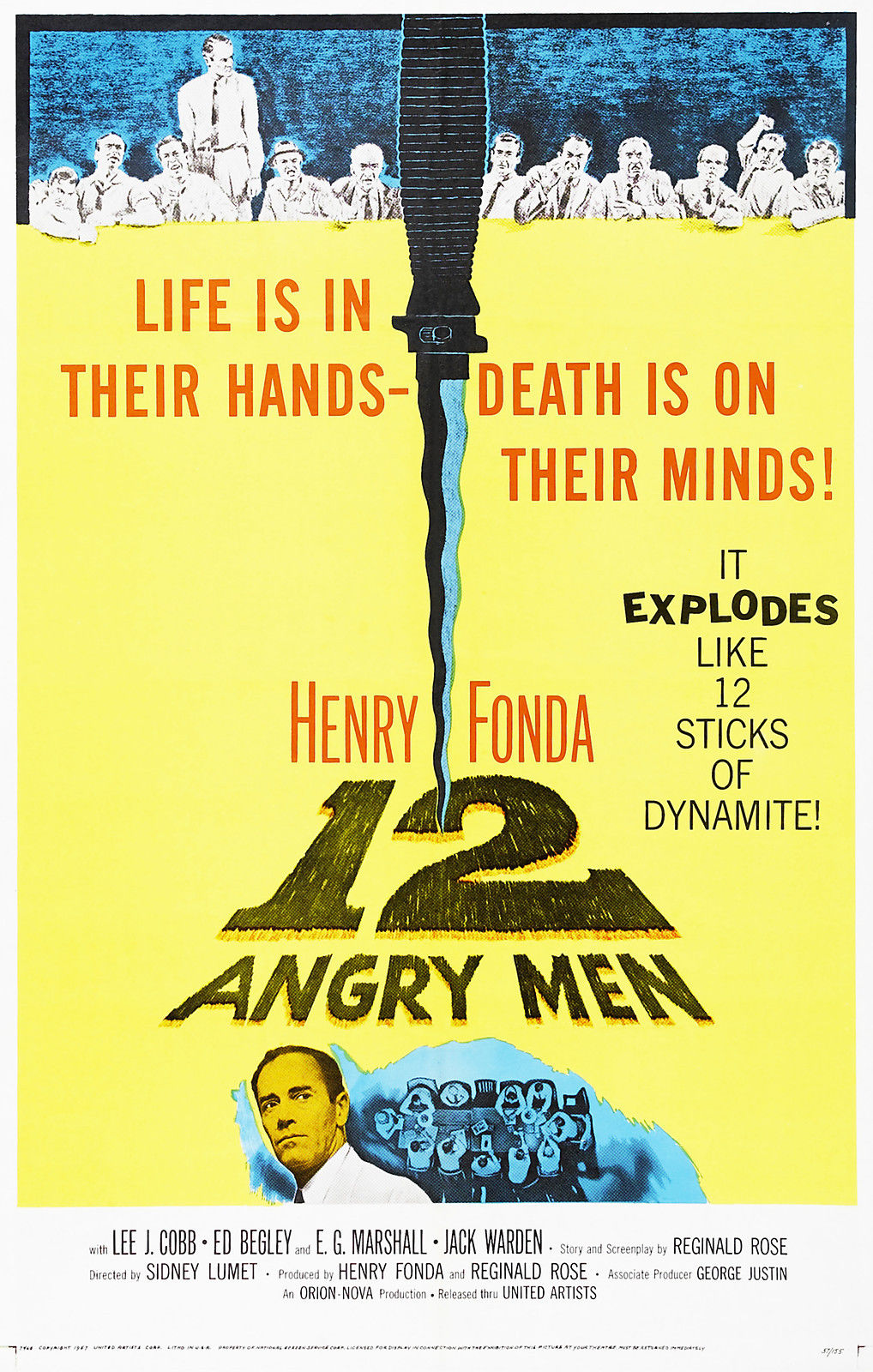

12 Angry Men *

Release: 1957 (United Artists)

Director: Sidney Lumet

Screenwriter: Reginald Rose

Cast: Henry Fonda, Lee J. Cobb, E.G. Marshall, Jack Klugman

12 Angry Men is a classic of filmmaking. Scarcely 90 minutes long, it is a taut and powerful story of jury deliberations in the case of an 18-year-old defendant charged with homicide. The screenwriter, Reginald Rose, got the idea while serving on a jury himself. Until then no movie had explored the dynamics of a jury deliberation.

As the title implies, all twelve jurors are men despite the fact that women had been serving on juries in New York, where the movie takes place, for twenty years beforehand. (To be sure, they were routinely excused on grounds of their “special obligation as the center of home and family life.”) Some high schools are producing the play nowadays under the PC-approved title 12 Angry Jurors, but the testosterone-teeming competitive jockeying among twelve men brings a special tension to the proceedings. (Incidentally, we have a strong preference for the original, 1957 production of this movie. The 1997 remake is good but not as good.)

Filmed in black-and-white to emphasize the binary decision any jury must render, often against myriad shades of gray, 12 Angry Men is an extraordinary movie for leadership. In particular, it is a case study in Socratic leadership—that is, leadership by means of asking a succession of provocative, probing questions that compel people to rethink their assumptions and beliefs. Juror No. 8 (Henry Fonda) has no official authority beyond that of the other jurors. He isn’t even the foreman. Yet he persuades his peers to reconsider their initial judgment of the accused. It is a good reminder that leadership doesn’t require a title. Moreover, the strength of No. 8’s argument arises not from overbearing, omniscient certitude but rather from intellectual humility. What he doesn’t know is every bit as important as what he does know. His earnest reservations, rather than his earnest presumption of guilt, give energy and force to his questions and cause the other jurors to think more critically and examine their own assumptions. Socratic leadership emerges as a counterintuitive but powerful tool.

Here are some questions and prompts about 12 Angry Men for your reflection:

What did you notice about styles of communication among the jurors? Which styles were most effective? The most ineffective?

Who showed leadership credibility and how? Who didn’t?

Who showed respect, honor, and trust for others? Who didn’t?

Who demonstrated empathy for others? Who didn’t?

What role did curiosity play in the jury's deliberations? In what character did you see it the most? In what character the least? What is the connection between curiosity and Socratic leadership?

How would you describe the jury foreman, Juror No. 1 (Martin Balsam), as a leader?

Whose courage grew as the story unfolded?

Passion and conviction are important vectors for leadership. Yet at least two of the jurors, No. 3 (Lee J. Cobb) and No. 10 (Ed Begley), were quite passionate in their convictions and yet wholly ineffective. How do you explain that?

How did Juror No. 8 (Henry Fonda) effectively lead the jury?

What does this movie tell us about effective leadership?

42: The True Story of an American Legend

Release: 2013 (Legendary)

Director: Brian Helgeland

Screenwriter: Brian Helgeland

Cast: Chadwick Boseman, Harrison Ford

You won’t see any professional baseball players wearing the number 42 on their jersey, ever again—except once a year, when every player on every team throughout the major leagues wears the same number. That is a tribute to Jackie Robinson, the great second baseman and aggressive base stealer who integrated the sport. This movie is the story of Robinson and Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers owner whose courage and foresight were instrumental to the sport and American culture. You’ll find lots to enjoy and more to admire in Boseman’s portrayal of Robinson and Ford’s depiction of Rickey. Both men were leaders of the first rank.

Apollo 13 *

Release: 1995 (Imagine Entertainment)

Director: Ron Howard

Screenwriters: William Broyles Jr. and Al Reinert

Authors of Book: Jim Lovell and Jeffrey Kluger (Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13)

Cast: Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton, Kevin Bacon, Gary Sinese, Ed Harris, Kathleen Quinlan

This movie, drawn from the harrowing Apollo 13 spaceflight, legendary for the line “Houston, we have a problem,” offers a compelling example of teamwork and collaboration. It emphasizes the importance of reaching deep down into an organization for expertise and insight not readily available or even known at the top. Besides, it’s a flat-out terrific movie. It won two of the nine Academy Awards for which it was nominated.

In the spring of 2018 I was lucky enough to meet with Jim Lovell, the commander of Apollo 13, for an in-depth conversation about leadership in crises. An account of our conversation is on my blog; just click on the Blog tab in the menu bar above. (See also my reviews of The Right Stuff and Rocket Men under Books on Leadership / Biographies, Memoirs, and Histories of Leaders.)

Here are some questions and prompts about Apollo 13 for your reflection:

What did you learn about leadership from this movie?

Who exercised primary leadership in a large way? Who exercised collateral leadership in a big way? (See the Glossary and Concepts under the Resources tab on this site for a fuller explanation of distributed leadership, primary leadership, and collateral leadership.)

The mission commander, Jim Lovell, made a key decision early in the movie to replace Ken Mattingly with Jack Swigert. Would you have done the same? Why or why not? Was Lovell not being loyal to Mattingly? What are a leader’s obligations to the team members in terms of loyalty?

At one point the NASA director warns that a disaster is imminent. Mission director Gene Kranz replies, “With all due respect sir, I think this is going to be our finest hour.” In my conversation with him, Jim Lovell singled out that comment, and he told me it was indeed NASA’s finest hour. What does that exchange say about the tension between pessimism and optimism in a leader’s mindset?

Though never uttered during the actual flight, Kranz’s comment that “failure is not an option” is a remarkable example of setting clear expectations and aspirations — a core duty of leaders. It is also a rare example of a negative adding strength to a declarative statement.

Babe

Release: 1995 (Kennedy Miller)

Director: Chris Noonan

Screenwriter: Dick King-Smith

Author of Book: George Miller (The Sheep-Pig)

Cast: James Cromwell, Magda Szubanski, Christine Cavanaugh

Just because this movie is splendid G-rated entertainment for the whole family doesn’t make it any less valuable as a tutorial in leadership, despite the fact that herding sheep is as horrifying a metaphor for leading people as you can imagine. It’s a terrific movie, too; my friend and former colleague, movie critic Dann Gire, memorably called it “the Citizen Kane of talking pig movies.”

Babe takes place on Farmer Hoggett’s sheep farm in Australia. Babe, the star of the movie, is an anthropomorphous pig with a vision, a soul, and a voice, though it must be said that in this movie all the animals talk. Babe aspires not only to escape the roasting pan and dinner table of Christmas Day but also to assume the mantle of a sheepdog, first among equals on any sheep farm.

Alas, as a pig, Babe lacks a certain way with sheep. Unlike sheepdogs, who intimidate sheep by running and snarling, Babe can only waddle and snort. The sheep, not so dumb as they look, just stand there and laugh when Babe tries to order them around by growling. Meanwhile, the supercilious sheepdogs huff: Never send a porcine to do a canine’s work.

Babe perseveres. The runt of his litter, he is determined to rise to the top. If he lacks a bark and a credible growl, at least he has humility, a self-deprecating sense of humor, and a certain respect for the sheep. Moreover, he intuitively knows or gradually learns a few important things about leadership communication. Above all, he senses that the dignity and self-respect of the sheep are very much worth preserving.

Babe comes to understand that leadership—and communication in the service of leadership—ultimately has a lot to do with behavior; that, for a leader, both the purpose and the means of communication come down to behavior. He realizes that leadership is not so much a matter of asserting one’s own will as it is of engaging the common will of others. And he understands that respectful communication is the lifeblood of that process. It is very nearly the art of leadership itself. It is who we are and what we do. It is the respect and honor we pay to others, by deed as well as by word.

Finally, Babe learns that the role of a leader is all about inspiring and directing the discretionary, principled effort of followers. Just as Stephen Covey exhorts us to seek first to understand, Babe knows that as a leader he must first demonstrate his own commitment before enlisting the commitment of others. For anyone aspiring or carrying out the work of leadership, Babe offers big lessons on dignity, respect, and communication.

Chariots of Fire

Release: 1981 (Allied Stars)

Director: Hugh Hudson

Screenwriter: Colin Welland

Cast: Ben Cross, Ian Charleson, Nicholas Farrell

Nominated for seven Academy Awards and winner of four (including best director and best screenplay), Chariots of Fire memorably illustrates integrity of leadership, institutional agility, and collegial cooperation. It tells the true story of Eric Lidell, a devout Christian and a Scottish sprinter who won a gold medal in 1924, after trading places with a teammate to avoid running on a Sunday.

Cool Hand Luke

Release: 1967 (Warner Bros.)

Director: Stuart Rosenberg

Screenwriters: Donn Pearce and Frank Pierson

Cast: Paul Newman, George Kennedy, Strother Martin

“What we have here, is a failure to communicate,” the road captain (Strother Martin) tells the impertinent prisoner (Paul Newman). Later, it is the prisoner’s turn to dish it right back to the road captain. While the movie is grand entertainment, it is famous for one of the most useful quotations about communication in circulation today. The failure to communicate clearly, credibly, and coherently is the No. 1 problem that organizations of any appreciable size face.

Darkest Hour

Release: 2017 (Focus Features)

Director: Joe Wright

Screenwriter: Anthony McCarten

Cast: Gary Oldman, Lily James, Kristen Scott Thomas

Nominated for six Academy Awards and, in my opinion, deserving of one more for Lily James’s nuanced portrayal of a stenographer, Darkest Hour is the absorbing, true story of Winston Churchill’s early weeks as the United Kingdom’s wartime prime minister, as the British troops are cornered at Dunkirk during the Battle of France. Those weeks in May and June 1940 witnessed four of history’s finest orations, which played a mighty role in mustering the British will to fight the Nazi war machine with little of their own. Near the end of the movie, moments after Churchill has finished another rousing speech to Parliament, someone leans over and asks the anti-war Lord Halifax what just happened. Halifax despairingly replies: "He mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” (The line was actually not spoken by Lord Halifax but rather by the American television journalist Edward R. Murrow, in a broadcast tribute to Churchill on his eightieth birthday in 1954, and employed again in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy granted Churchill honorary American citizenship.) Despite the errant quote, history buffs will love this movie, and anyone with an interest in leadership—especially those who buy into the Great Men thesis advanced by Thomas Carlyle in 1840—will have plenty to think about afterward.

Dead Poets Society

Release: 1989 (Touchstone)

Director: Peter Weir

Screenwriter: Tom Schulman

Cast: Robin Williams, Robert Sean Leonard, Ethan Hawke

Robin Williams is a teacher in an all-boys prep school in Vermont who embraces unorthodox pedagogical methods, such as asking his students to stand on his desk to view the classroom differently. He encourages the students to think for themselves and reject stupid instruction, such as applying a mathematical formula to judge the quality of poetry. Dead Poet’s Society is a wonderful endorsement of unique, ad hoc leadership.

Death of a Salesman

Release: 1985 (Roxbury)

Director: Volker Schlöndorff

Screenwriter: Arthur Miller

Playwright: Arthur Miller

Cast: Dustin Hoffman, Kate Reid, John Malkovich, Stephen Lang

We prefer this made-for-TV movie over the 1951 original for the powerful acting by Dustin Hoffman in the role of down-and-out salesman Willy Loman and by John Malkovich as his son Biff. The movie, and the 1949 play on which it is based, dramatically illustrates the extent to which one’s career and self-identity overlap. Perhaps the most eloquent and most haunting line belongs to Willy’s wife, Linda: “Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a man.”

The Devil Wears Prada *

Release: 2006 (Twentieth Century Fox)

Director: David Frankel

Screenwriter: Alene Brosh McKenna

Author of Book: Lauren Weisberger (The Devil Wears Prada)

Cast: Meryl Streep, Anne Hathaway, Stanley Tucci, Simon Baker, Emily Blunt

Meryl Streep stars as every employee’s worst nightmare: a boss who is at turns loud, demeaning, arrogant, demanding, ruthless, and worse. Even as it illustrates awful leadership, this movie offers important lessons in respect, dignity, empathy, and other aspects of genuine engagement in the workplace.

Here are some questions and prompts about The Devil Wears Prada for your reflection:

Let’s take a step back before we take a step forward. Why should we study bad leadership in order to understand good leadership? More generally, why should we examine the opposite or the negation of an ideal as a means of understanding the ideal itself? How does it help?

The Devil Wears Prada is a splendid movie to illustrate bad leadership. Why is that?

The character of Miranda Priestly in this movie is an extreme caricature. Have you ever worked for someone with anything even remotely close to her hubris and caprice? For anyone whose leadership is widely acknowledged as bad in one or more of Barbara Kellerman’s seven kinds? (The reference is to Kellerman's book Bad Leadership, which students read in conjunction with this movie.)

Which of Kellerman’s seven kinds of bad leadership does Miranda Priestly reflect? In what ways? Please cite examples from the movie.

Can you think of other kinds of bad leadership that Miranda Priestly embodies?

Is there a difference between the competence or incompetence with which Miranda Priestly edits the magazine, on the one hand, and the competence or incompetence with which she leads, on the other? How common do you think that is? How much of a problem is it for the “leader” and her self-awareness?

What are the effects of such bad leadership on an organization? Can you conjure up a financial or operational impact?

Andy changes her behavior, and perhaps even her self-identity, to please her boss, but it costs her the support of her friends. To what extent does this occur in real life when we change ourselves because we are intent on following someone — or because we are choosing a new course of action for ourselves, as we follow our own leadership of ourselves? What social price — think of it as an opportunity cost — do leaders pay for their bad leadership? What price — or opportunity cost — do followers pay for their bad followership?

How do you suppose a follower might best follow a leader who is self-important and self-indulgent?

Doubt

Release: 2008 (Miramax)

Director: Scott Rudin

Screenwriter: John Patrick Shanley

Playwright: John Patrick Shanley (Doubt: A Parable)

Cast: Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, Viola Davis

Another splendid movie starring Meryl Streep, Doubt illustrates the moral complexity of leadership when accurate, complete information is never at hand. All four principal actors and the screenwriter were nominated for Academy Awards. (See also my review of Spotlight, another movie that explores the tragedy of priestly pedophilia, below.)

Elizabeth

Release: 1998 (Polygram)

Director: Shekhar Kapur

Screenwriter: Michael Hirst

Cast: Cate Blanchett, Geoffrey Rush, Christopher Eccleston

Few films have captured palace intrigue better than this one. Elizabeth, who ascends to the throne of England on the passing of her half-sister Mary, is Protestant, and she makes no apology for her opposition to Rome’s influence. In the early days of her reign she must sort out the people around her to determine who may stay and who must go.

Enron: The Smartest Guys In the Room *

Release: 2005 (Magnolia Pictures)

Directed by: Alex Gibney

Authors of Book: Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind (The Smartest Guys In the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron)

This documentary will be the closest that most people get to understanding how Enron grew so fast and collapsed even faster. Only 110 minutes long, it cuts through the gibberish and gobbledygook to tell a story of me-first greed, willful pride, unchecked arrogance, and deliberate deceit at the bottom of the accounting scandal that brought down America's seventh-largest corporation. It addresses and ultimately answers a simple question: "Was [the collapse of] Enron the work of a few bad men, or the dark shadow of the American Dream?" More than a story about numbers and financial statements, or even a history of reckless deregulation and "inside baseball," Enron is a story about people—some of whom think they are above the law and too good to bother with others. We see Ken Lay, the company's founder and board chairman who died six weeks after his conviction; Jeff Skilling, its brash, profane chief executive officer who was released from prison in 2018 after serving eleven years of a fourteen-year term (reduced from an original sentence of twenty-four years); Andrew Fastow, the chief financial officer and mastermind of numerous shell companies created to hide Enron's $30 billion debt, who served five years, and more. A.O. Scott, a movie critic for the New York Times, called this production "indecently entertaining," and were it not for the fact that many thousands of people lost their retirement savings, careers, mortgages and college education for their kids, it would be. It is still instructive, and it's a case study in what can happen when leadership itself is either amoral or immoral.

Here are some questions and prompts about Enron for your reflection:

In what ways did Kenneth Lay, Jeffrey Skilling, and others create new expectations about the company and its performance? Was that merely an exercise in public relations and shareholder relations? Was it a legitimate act of leadership?

Many if not most companies proclaim the importance of integrity as a core value. Enron itself did. How can leaders operationalize integrity, so as to make certain it is not merely honored in the breach? How should leaders incorporate ethical concerns in their decision making?

What is the role of the Milgram Experiment in explaining the Enron culture? Do you think it explains or helps explain the company's downfall?

Think of some leaders you would regard as strong. What is a strong leader? Did you see any strong leaders in this film?

In the epilogue to the film, the narrator paints a picture of outsized ambition morphing into fraud and deceit. How could effective leadership have reined it in?

Enron's slogan was ASK WHY. Why do you think the whole affair occurred?

The Founder

Release: 2016 (Weinstein Brothers)

Directed by: John Lee Hancock

Screenwriter: Robert D. Siegel

Cast: Michael Keaton, Laura Dern, Nick Offerman, John Carroll Lynch

Although it was snubbed by the Academy Awards and lost money at the box office, The Founder is one of the better biopics ever produced. It’s the story of Ray Kroc (Michael Keaton), who discovered a prototypal fast-food restaurant in San Bernardino and built it into the global behemoth of McDonald’s Corporation, which feeds 1 percent of the world’s population every day.

This movie has phenomenal attention to detail—everything from the name of a street in Des Plaines, Illinois, where the first corporate restaurant opened, to the distinctive shape of windows in the company’s headquarters, to Kroc's membership in the Rolling Green Country Club and his preference for Canadian Club—and yet it also nails the big aspects of Kroc's character, the company's shaky beginning, Kroc's turbulent relationship with the McDonald brothers, and the creation of a new business model. Having lived for twenty years in Arlington Heights, Illinois, where Kroc was living when he seized on the idea, and having heard countless stories from local oldtimers about him, I can attest to the veracity of the film.

Gandhi *

Release: 1982 (Columbia Pictures)

Director: Richard Attenborough

Screenwriter: John Briley

Cast: Ben Kingsley, Candice Bergen, Edward Fox, John Gielgud

An epic (and at 183 minutes a very long) film, Gandhi is the life story of Mohandas K. Gandhi, from his humiliation in South Africa in 1893 to his assassination in New Delhi in 1948. The very personification of authenticity and humility in leadership, Gandhi to this day remains the world’s greatest apostle of non-violent political protest. Still, there are many serious questions as to the applicability of his philosophy, known as satyagraha, to situations in which the oppressed face ruthlessly violent oppressors, and there are widespread doubts about the legacy Gandhi left behind. This biopic presents him as a human whose acumen in leadership grows over time, and whose appreciation of his capacity to inspire people morally is central to his impact. (See also my review of Gandhi’s memoir, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, in Books on Leadership / Biographies, Memoirs, and Histories of Leaders.)

Here are some questions and prompts about Gandhi for your reflection:

On the basis of Attenborough’s movie, and of anything else you have read or understood about Gandhi, what did he know about leadership — intuitively or empirically — that others seem not to have known?

Would you call Gandhi a charismatic individual? What is charisma, anyway? How did its originator, the German sociologist Max Weber, intend it to be understood a century ago, and how does that meaning differ from its popular meaning today?

How did Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa prepare him for leadership in India?

Was Gandhi’s choice of handmade robed attire essential to, complementary to, incidental to, antithetical to, or irrelevant to his leadership? In what way? Can you think of another famous, historic leader who used his attire in the opposite way — as a means of garnering respect and admiration?

Of what significance is cultural and historical context to Gandhi’s success—specifically, British classism and condescension to Indians, the turbulence of World War II, the historical erosion of European imperialism worldwide?

What does the Gandhi case say, if anything, about the Great Man Thesis advanced in 1840 by Thomas Carlyle? What would Herbert Spencer have thought twenty years later? Why is that important to you in the twenty-first century?

Glengarry Glen Ross

Release: 1992 (New Line)

Director: James Foley

Screenwriter: David Mamet

Playwright: David Mamet

Cast: Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alec Baldwin, Ed Harris, Kevin Spacey, Alan Arkin

David Mamet has few peers in the art of writing earthy dialogue for the stage and screen. If you can get past the profanity, Glengarry Glen Ross offers a wealth of insight on motivating (and its dubious counterpart, manipulating) employees. Whatever you see in this movie, do just the opposite, and you’ll probably be fine.

Henry V

Release: 1989 (BBC)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

Screenwriter: Kenneth Branagh

Playwright: William Shakespeare

Cast: Kenneth Branagh, Derek Jacobi

The young king of England leads an outgunned, outmanned army on an invasion of France in the Hundred Years War, as memorialized by William Shakespeare. Before the bloody Battle of Agincourt of 1415, Henry rallies the English troops with a memorable speech: “We few, we happy few, we merry band of brothers, for he today that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.”

High Noon

Release: 1952 (United Artists)

Director: Fred Zinnemann

Screenwriter: Carl Foreman

Cast: Gary Cooper, Grace Kelly, Lloyd Bridges, Henry Morgan

Far from the archetypal Western with gunfights, Indians, and cattle drives, High Noon is a study in moral leadership. Gary Cooper, in an Oscar-winning performance, portrays a marshal who must face an outlaw bent on killing him. He finds little support among the townspeople. Any leader who has tried in vain to arouse a slumbering constituency can relate.

Hoosiers

Release: 1986 (Orion)

Director: David Anspaugh

Screenwriter: Angelo Pizzo

Cast: Gene Hackman, Barbara Hershey, Dennis Hopper

This is an exquisite movie, easily one of the best sports movies ever made and one of the most inspirational as well. It is a loving reminder of three truths: that leadership comes in many forms and often from least-expected sources, that leadership builds a community of highly engaged people, and that leaders both need and nurture people who care enough to do extraordinary things.

I Love Lucy: “Job Switching”

First Broadcast: 1952 (Desilu)

Director: William Asher

Scriptwriters: Jess Oppenheimer, Madelyn Pugh, and Bob Carroll Jr.

Cast: Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, Vivian Vance, William Frawley

One of the funniest television episodes ever broadcast, “Job Switching” had the husbands (Desi Arnaz and William Frawley) stay home and do the cooking and laundry while their wives (Lucille Ball and Vivien Vance) went to work in a chocolate factory, thus setting up the legendary scene on the conveyor belt. The program raises all kinds of good questions about the workplace, from the ever-increasing demands of the factory supervisor to the assumptions the men make as homemakers and cooks.

Invictus *

Release: 2009 (Warner Bros.)

Director: Clint Eastwood

Screenwriter: Anthony Peckham

Author of Book: John Carlin (Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and The Game That Made a Nation)

Cast: Morgan Freeman, Matt Damon

Power and example are often at odds in leadership. There is a tension between them. Managers face a basic choice: Do you lead by the example of power, or do you lead by the power of your example? Can you do both? This inspiring movie, based on the true story of the South African Springboks in the World Cup of rugby in 1995, illustrates that tension. Leaders are often in a situation where they must exercise power. What they rarely appreciate is the fact that the very exercise of power can reinforce their impact as a leader, or it can do just the opposite: it can compromise it, even undermine it. Which it does depends on context, intent, and clear, compelling, credible communication.

Here are some prompts and questions on Invictus for your reflection:

What is the significance of the couplet, “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul”? In particular, what does it say to an aspiring leader?

Think about the difference between influence and inspiration. What is it? Why is the difference of any interest to us? How does a leader wield influence? How does she inspire?

As Hendrick, one of the Afrikaner security guards, escorts François Pienaar to President Mandela’s office to meet with Mandela, there is a revealing dialogue that may have been difficult to understand. I myself went to the screenplay to understand it. Pienaar asks the guard what Mandela is like. Hendrick replies: "When I worked for the previous president, it was my job to be invisible. This president, he found out I like English toffee and brought me some back from his visit to the Queen. To him, nobody is invisible." What is the significance of this dialogue? Of visibility?

Rewatch the scene in Mandela’s office, when he welcomes Pienaar, beginning at 45:45. Why do you think Mandela invited Pienaar to tea? How would you have answered Mandela’s twin questions: “Tell me, Francois, what is your philosophy of leadership?” and “How do you inspire your team to do their best?” After Pienaar replies that he has always believed it important to lead by example, Mandela pressed on: “But how to get them to be better than they think they can be? That is very difficult, I find. Inspiration, perhaps. How do we inspire ourselves to greatness when nothing less will do? How do we inspire everyone around us? I sometimes think it is by using the work of others.” What was he implying? How do you think leaders can inspire people to greatness?

In the same scene, Mandela goes on to tell Pienaar about the effect that the poem, Invictus, had for him when he was imprisoned on Robben Island. “It helped me stand up when all I wanted to do was lie down.” Pienaar understands intuitively. Mandela shares the anecdote of the Olympic Games in Barcelona, when he was greeted by the crowd singing the anthem, Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. “We need inspiration, François. Because in order to build our nation, we must all exceed our own expectations.” What is he doing here? Why?

Notice the emphasis Mandela put on expectations. What is the difference between expectations, even for oneself, and aspirations? How can a leader create expectations that people embrace as new aspirations?

Why do you think Mandela wanted the Springboks to conduct coaching clinics in the townships across South Africa?

What was the point of taking the Springboks to Robben Island prior to the tournament? What do you think happened to the players as they toured the prison? How does this scene tie to the conversation in Mandela’s office?

It’s a Wonderful Life *

Release: 1946 (RKO)

Director: Frank Capra

Screenwriters: Frances Goodrich, Albert Hackett, and Frank Capra

Cast: James Stewart, Donna Reed, Lionel Barrymore

A saccharine but beloved holiday classic in the United States, It’s a Wonderful Life is set in idyllic Bedford Falls on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing Great Depression. It stars James Stewart as George Bailey, whose father (played by Samuel S. Hinds) is president of the Bedford Falls Building and Loan (also commonly known as a thrift institution or an S&L, for savings and loan) until he dies of a stroke. The S&L’s solvency is threatened by hard times and the greed of the richest man for miles around, Henry F. Potter, a crochety old coot (played by the legendary Lionel Barrymore) who owns the town’s competing bank and sits on the S&L’s board of directors.

One of the truly iconic movies ever made, It’s a Wonderful Life succeeds on so many levels, not the least by illustrating the potential for good and evil by financial institutions and, for that matter, businesses of any kind. “Pottersville” has since become a synonym for a dystopian place, “Bedford Falls” for a blissful, utopian community, and George Bailey and Henry Potter for the best and worst of businessmen.

As you watch this movie, think about these questions:

About 11 minutes into the film, George and his father are seen at the family dining table discussing George’s future. Keep in mind our definition of leadership as revolving around setting new expectations and championing them with such conviction that other people adopt and embrace them as aspirations for themselves. Followers genuinely want what the leader wants, not as a matter of manipulation but as the fruit of the leader's inspiration by word and deed. Of these two figures, George and his father, is either man filling the role of a leader? Neither? Both? How or how not? Why or why not?

After Pa Bailey dies, we see a meeting of the S&L’s board of directors. Mr. Potter moves to dissolve the thrift. George Bailey delivers a sharp retort. Later, at about 57 minutes, George faces down a run on the S&L. He pleads with the depositors to give the thrift time to overcome a cash crisis. How do these two monologues rise to leadership?

At about 40 minutes, we see George smoking a cigarette on a summer evening. His mother (Beulah Bondi) comes out, and in the ensuing conversation she encourages him to call on Mary Hatch (Donna Reed), who is home from college. Is this an act of leadership? If so, how?

George sacrifices his dream of a college education, worldwide travel, and an important career for the community and its savings and loan. How should we think about personal sacrifice and leadership? Do they necessarily go hand in hand? In your own experience, can you point to leaders who have sacrificed their own dreams for the well-being of others? How does this conflict with conventional notions of leaders and leadership?

How does George’s guardian angel Clarence (Henry Travers) exercise leadership? [As George contemplates suicide, Clarence shows him the values of his life—how he has positively affected the lives of his friends and neighbors and the community of Bedford Falls as a whole. In doing so, he is setting a newfound appreciation, and therefore new expectations and aspirations, for George. Remember what Steve Jobs taught us about marketing: “Sometimes you have to show people what’s possible. The same is true for leadership.]

Overall, what did you learn about leadership from this movie?

The King’s Speech *

Release: 2010 (Weinstein)

Director: Tom Hooper

Screenwriter: David Seidler

Cast: Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush, Helena Bonham Carter, Derek Jacobi

Winner of four Academy Awards (best director, picture, actor, original screenplay), The King’s Speech tells the dramatic, true story of Britain’s King George VI (Colin Firth), who inherited the throne after his father died and his older brother abdicated eleven months later. The accidental new king must overcome a serious speech impediment. Through the warm-hearted coaching of Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), the monarch manages to give a stirring, inspirational speech by radio to a worldwide audience on the eve of World War II. Few leaders suffer from speech pathologies, but many have great reluctance or inability to speak publicly, especially in an inspirational vein, and therefore avoid it altogether. That seriously limits their impact.

Here are some questions and prompts about The King's Speech for your reflection:

Few people and even fewer leaders suffer from speech impediments. How is The King’s Speech nonetheless relevant for leaders and aspiring leaders?

In a scene prior to his death, King George V talks about the impact of radio on the role of leaders in the 20th century. What did he say, and why is it important even today? What are some of today’s analogues to radio in the 1930s? How does technology affect the work of leaders?

Lionel Logue, the speech therapist, proves to Prince Albert that he doesn’t stammer when he sings or when he cannot hear himself as he listens to Mozart’s “Overture to La Nozze di Figaro” while reading an excerpt from Hamlet. We also see that the prince stammers little or not at all when telling a bedtime story to his children. What is the significance of all that?

Logue insists on equality between himself and Prince Albert from the start, but he does not receive it. As they walk through Regent’s Park, the prince berates Logue as a mere commoner — the son of a brewer, not the son of a king. What is the effect of that on Logue, and what does it say about the challenge of leadership? (Note that the prince is excoriating Logue here for treason in suggesting that he is his brother’s better, but at another point is silent when Churchill similarly suggests that he prepare for the monarchy.)

Bertie tells Logue: “You know, Lionel, you’re the first ordinary Englishman (though he’s actually an Australian) I’ve ever spoken to. Sometimes, when I ride through the streets and see, you know, the Common Man staring at me, I’m struck by how little I know of his life, and how little he knows of mine.” How should we think of the dynamic of distance — psychological, social, economic, even physical — between the leader and the led?

Prince Albert pays a visit to No. 10 Downing Street after his father dies and his brother, now King Edward, ascends to the throne. Referring to the new king, who wishes to marry a twice-divorced American woman, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin poses a fundamental question: “Does the king do what he wants, or does he do what the people expect him to do?” What are the implications of that question on leadership in general? How do you answer it as a matter of general principle? How would you answer it if you were the king? Why is the question important to us as students of leadership?

Now, keeping in mind Baldwin's remark, reconcile it, if you can, with a profound observation by one of his 19th century predecessors, Benjamin Disraeli, who said: "I must follow my people. Am I not their leader?" Where does that take you? What insights does it generate?

Logue counsels King George VI that he need not be afraid of his father, who is dead, or of his brother David, who has abdicated. “You don’t need to be afraid of the things you were afraid of when you were five,” Logue tells him. What is the significance of this dialogue? Think of some well-known leaders. Does their leadership reflect their psychological state? To what extent do you think a residual fear might drive them to think, say, or do things that an emotionally mature and healthy person would likely not — or vice versa?

What are the messages of this film in its totality?

Lawrence of Arabia

Release: 1962 (Columbia Pictures)

Director: David Lean

Screenwriters: Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson

Author of Book: T.E. Lawrence (Seven Pillars of Wisdom)

Cast: Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, Omar Shariff

As much as anyone in the twentieth century, T.E. Lawrence was responsible for the Middle East as we know it. Until he ventured on camelback into the Arabian peninsula, it was a vast desert of warring tribes under the thumb of the Ottoman Empire. He united the tribes and introduced guerrilla warfare to the Mideast, and together the Arabs beat back their Turkish oppressors.

Directed by David Lean and starring Peter O’Toole in his breakout role, this movie is still exquisite a half-century after it was filmed. (The playwright Noel Coward said of O’Toole’s visage, “If he were any prettier, they would have had to call it Florence of Arabia.”) It is filled with fabulous scenes of the desert. Though I was too young to enjoy it when it premiered in 1962, I have watched it twice as an adult—first at home on DVD, then on the big screen at a Fathom Events production. It is true that the film takes a few liberties with history, but that is inevitable. The movie still grandly illustrates Lawrence’s impertinence and creativity, and it vividly captures the environment in which he worked. A real epic, it is four hours long—when was the last time you viewed a movie with an intermission?—and yet it grabs you from the start and doesn’t let go.

History buffs will want to supplement it with either Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia by Michael Korda or Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East by Scott Anderson.

Lean On Me

Release: 1989 (Warner Bros.)

Director: John G. Avildsen

Screenwriter: Michael Schiffer

Cast: Morgan Freeman, Beverly Todd, Robert Guillaume

This is the inspirational, real-life story of Joe Louis Clark, an unconventional educator who is hired in a last-ditch effort to prevent Eastside High School in Patterson, New Jersey, from going into receivership. The school is plagued with gang violence, drug abuse, and unacceptable test scores. Clark’s unorthodox methods make him both hero and villain, but he gets the job done.

Lincoln *

Production: 2012 (Touchstone, Dreamworks)

Director: Steven Spielberg

Screenwriter: Tony Kushner

Author of Book: Doris Kearns Goodwin (Team of Rivals)

Cast: Daniel Day-Lewis, Sally Field, David Strathairn

More books have been written and more movies filmed about Abraham Lincoln than anyone else in modern civilization, and for good reason. His life and his presidency offer timeless lessons in leadership, character, and communication. Steven Spielberg’s eponymous movie captures it all with color and verve. The film is excellent, and I urge everyone to see it.

Spielberg has said he wanted to make a movie about Lincoln for more than a decade, but he didn’t know how to squeeze so much material into a couple of hours. He got his answer when he read Team of Rivals, the marvelous book on Lincoln’s bipartisanship by Harvard historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. The final two chapters of that book focus on Lincoln’s single-minded advocacy, in early 1865 just weeks before his assassination, of the Thirteenth Amendment, which would ban slavery. (As a point of history, the constitutional amendment was necessary because the Emancipation Proclamation two years earlier had been a wartime measure, and therefore it would be of dubious legality after the war’s end.)

But here’s the crux of the matter: Lincoln’s re-election in November 1864 had long coattails. He would enjoy larger majorities in Congress beginning in March 1865. The commonsense thing to do was wait till then, when approval of the Thirteenth Amendment would be easier. Lincoln refused. He insisted on moving quickly. As he declares in the movie (portrayed exquisitely by Daniel Day-Louis), he wanted Congress to act “now, now, now!”

That is one of seven insights on leadership that I drew from the Spielberg production: Bring a sense of urgency to the important. If it’s important to do tomorrow, it’s important to do today. Do whatever you can now. Don’t wait, even when waiting would make things ostensibly easier. Do what you must do, do what you can do, and do it now.

Here are six other lessons on leadership that I took from the Spielberg movie:

Communicate through storytelling, analogies, metaphors, example, and anecdotes of personal experience whenever possible. Lincoln, like other leaders before and since, relied heavily on storytelling. Stories are powerful tools, because they give people a vivid way to remember a theoretical point. Our ancestors have been telling stories for millennia. We are hardwired to love stories. Lincoln knew it. Spielberg and Goodwin know it. As a leader, you must know it. And don't just settle for telling stories. Create them by living out your values in a visible way, for others to notice and remark upon. Be a story maker as well as a storyteller.

Go to the people whose support you need. Do not wait for people to come to you. Do not expect them to come to you. You must go to them, and you must listen first. Then speak to their concerns and issues. As a general rule, when you speak publicly, invoke their values and beliefs, and appeal to their nobility. People want to be about something larger than themselves. (It is true, as the movie illustrates, that Lincoln was not above scratching backs for votes. He knew his power, and he used it when he had to.)

Go on the offensive and stay there. Minimize your time on defense. This is as true in politics as it is in sports. Perhaps from his years of wrestling as a youngster, Lincoln intuitively knew the importance of offense. He would relearn that lesson militarily during the Civil War.

Recognize and accept practical limitations, and work within them. “Politics is the art of the possible,” Lincoln’s contemporary Otto von Bismarck would say a few years later. That is not a license to do nothing. Rather, it is worldly acknowledgement that the perfect can be the enemy of progress. In the movie, Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), who knows that people are inherently equal, is forced to say in House debate that he favors equality of legal rights only. Had he claimed more, the Thirteenth Amendment might very well have lost.

Know that ideas have consequences, and the consequences can be grave. The movie is filled with poignant scenes. One of them involves the president’s son Robert watching soldiers dump a barrow of human limbs in a mass grave. Another shows the president on horseback touring a battlefield of human carnage. There are more. For us, too, even in our day-to-day business, even in comparatively modest endeavors, ideas can have consequences from livelihoods to security in retirement to more. Never dismiss an idea as “merely a theory.” Ideas matter.

Abandon the pretense of perfection. We are all human. Few historical figures rival Lincoln for integrity, but even Lincoln was an imperfect man. There is evidence he fudged on an expense account as a congressman, and he could stretch the truth when he wanted. He pulled rank as commander-in-chief to discourage his son Robert from joining the military; and when he lost that argument, he inveigled General Ulysses S. Grant to give Robert a safe sinecure. This is not to excuse or justify such behavior, only to acknowledge the imperfectability of the human animal.

Malcolm X

Release: 1992 (Largo, JVC)

Director: Spike Lee

Screenwriters: Arnold Perl, James Baldwin, Spike Lee

Author of book: Malcolm X with Alex Haley (The Autobiography of Malcom X)

Cast: Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Al Freeman, Jr.

Cameos: Bobby Seale, the Rev. Al Sharpton, and Nelson Mandela

At three and a half hours, Malcolm X could easily have been—and more than one critic argued it should have been—two or even three movies. Director Spike Lee seemed unable to yell "Cut!” Still, its length is not sufficient reason to deny yourself the important lessons in history, culture, and leadership that this movie offers. Born Malcolm Little in 1920s Omaha, the protagonist (Denzel Washington) undergoes a prison-cell conversion and emerges as a disciple of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman, Jr.). He proves to be an incendiary orator. After a trip to Mecca, however, he realizes that Muslims are of many nationalities and races. His renunciation of the Nation of Islam has fatal consequences for the 39-year-old leader. Beyond telling the remarkable story of its protagonist and his times, Malcolm X sheds light on the journey of leadership and on the cultural contexts in which leaders exert influence.

A Man for All Seasons

Release: 1966 (Columbia Pictures)

Director: Fred Zinnemann

Screenwriter: Robert Bolt

Playwright: Robert Bolt

Cast: Paul Scofield, Wendy Hiller, Robert Shaw

Winner of six Academy Awards (for best picture, director, screenplay, actor, cinematography, costumes), A Man for All Seasons is the story of Thomas More, lord chancellor of England, who refuses out of conscience to support King Henry VIII’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon and marriage to Anne Boleyn, and ascension as supreme head of the Church of England. A classic tragic hero, More pays with his mortal life for his choice of political rather than religious heresy.

McFarland, USA *

Release: 2015 (Walt Disney, Mayhem)

Director: Niki Caro

Screenwriters: Christopher Cleveland, Bettina Gilois, Grant Thompson

Cast: Kevin Costner, Mario Bello, Ramiro Rodriguez

After losing his position at an Idaho school, Jim White (Kevin Costner) lands a job as an assistant football coach in the impoverished San Joaquin Valley community of McFarland, California. He has a rocky start, capped by a 63-0 defeat. Sitting in the bleachers, he notices that some of the boys on the field could compete in cross country. He builds the team and so inspires the students that they rise to the challenge. This true story is both mesmerizing and inspiring. Now grown, some of White’s former students are teachers today in McFarland, and White still lives there. Ken Blanchard, a highly regarded author and thinker on leadership, singles out this feel-good movie for its profound lessons on servant leadership.

Here are some questions and prompts on McFarland, USA for your reflection:

How many instances of servant leadership can you find in this movie? What are they?

In particular, how did Coach Jim White (Kevin Costner) serve? How many instances of his stewardship can you list?

In what ways did the cross-country runners serve Coach White, their community, and one another?

In your opinion — and there is no one right answer — what was the single biggest act of servant leadership in this movie?

What are some of the hurdles or challenges that servant leadership must meet? How were they depicted in the movie?

Writing about Jim White, Sports Illustrated magazine declared: "He rarely raised his voice. He'd stumbled upon the sorcerer's stone of coaching: Give so much of yourself that your boys can't bear to let you down." What would this look like in the context of your own servant leadership?

Moneyball

Release: 2011 (Sony Pictures)

Director: Bennett Miller

Screenwriters: Aaron Sorkin, Steven Zaillian

Author of book: Michael Lewis (Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game)

Cast: Brad Pitt, Jonah Hill, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Robin Wright

Quite literally, Moneyball is the inside-baseball story of Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), the general manager of the Oakland A’s major league baseball team and the foremost advocate of Sabermetrics, a statistical methodology that prioritizes hard data over soft intuition. Beane’s successful advocacy of Sabermetrics was a case study in leadership; he overcame more than a century of reliance on intuition to identify and recruit promising young players. Today almost every professional baseball team — along with teams in basketball, hockey, football, and soccer — use their own versions of Sabermetrics. Fans of the Chicago Cubs need not be told how much difference it made for their team in 2016. Michael Lewis and Aaron Sorkin faced a big challenge in writing a book and screenplay about a statistical methodology, but they succeeded magnificently.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington *

Release: 1939 (Columbia Pictures)

Director: Frank Capra

Screenwriters: Lewis R. Foster and Sidney Buchman

Author of Book: Lewis R. Foster (The Gentleman From Montana)

Cast: James Stewart, Jean Arthur, Claude Rains, Thomas Mitchell

Few movies have captured the angst of representative democracy better than Frank Capra’s Oscar-winning drama Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, starring James Stewart as Jefferson Smith, a naive, simple Everyman who is thrust into a world of moral ambiguity and turbidity.

An affable scouting leader dedicated to the well-being of kids, Smith is stunned when Governor Hubert “Happy” Hopper (Guy Kibbee) plucks him from obscurity to succeed a deceased U.S. senator. On arriving in Washington, the callow Mr. Smith finds himself dazzled by marble buildings and granite statues. He learns the ropes at the hands of his cynical, seen-it-all secretary (Jean Arthur as Clarissa Saunders), who tutors him in the arcane arts of writing legislation and eventually of filibustering the Senate to a halt, and who falls in love with him.

This movie illustrates all five of our analytical perspectives, or lenses, on leadership (for a fuller explanation of these lenses see Glossary and Concepts under the Resources tab on this site) as a matter of position and platform (Governor Hopper and the Senate president, played by Harry Carey), power and promise (machine boss Jim Taylor, played by Edward Arnold, and the scruffy reporter Diz Moore, played by Thomas Mitchell), persona and people (primarily Senator Joseph Paine, played by Claude Rains), prominence and performance (the governor and the senators), or purpose, principle, and process (especially Smith and Saunders). Though it can be criticized for its simplistic and Manichaean view of American politics, Mr. Smith has stood the test of time. It was released in 1939, the year widely regarded as the zenith of Hollywood’s glorious history for Gone With the Wind (directed by Victor Fleming and George Cukor), The Wizard of Oz (by Fleming and Cukor as well), Stagecoach (by John Ford), Goodbye Mr. Chips (by Sam Wood and Sidney Franklin) and more, and it has evolved into a morality tale on leadership. If you haven’t yet seen it, just wait and it will reappear on Turner Classic Movies with a marvelous commentary before and after the film by host Ben Mankiewicz.

Here are some questions and prompts on Mr. Smith Goes to Washington for your reflection:

Who emerged as leaders in the story? How did they create new expectations and inspire people to embrace them as aspirations for themselves? (See the Glossary and Concepts under the Resources tab on this site for an explanation of the importance of expectations in leadership.)

Which leaders were operating at the absolute archetype, the traditional archetype, the modern archetype, or the dynamic archetype? How? (See the Glossary and Concepts again.)

What role did communication play as the energy of leadership? How?

If leadership emerges in the space between leader and led, and if real leadership is in the eye of the beholder, where did it emerge here, and which beholders beheld it?

We often assert that leadership begins and ends in community. What examples of that can you find in this movie?

In the contest of wills between innocence and savvy, does innocence have any advantages? Is cynicism always the shrewder choice?

Are threats, intimidation, and manipulation effective tools for a leader? Why or why not?

Power has been defined as the capacity to say no. Do you agree or disagree with that simple definition? Why?

Mutiny on the Bounty

Release: 1935 (MGM)

Director: Frank Lloyd

Screenwriter: Talbot Jennings, Jules Furthman, Carey Wilson

Authors of Book: Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall (Mutiny on the Bounty)

Cast: Charles Laughton, Clark Gable

A classic in its own time, Mutiny on the Bounty is a lasting reminder that leaders cannot assume the loyalty of putative followers but rather must earn it. And re-earn it daily. Abusing and disrespecting one’s would-be followers is, to say the least, counterproductive.

Network

Release: 1976 (United Artists)

Director: Sidney Lumet

Screenwriter: Paddy Chayefsky

Cast: Faye Dunaway, Peter Finch, William Holden, Robert Duvall, Ned Beatty

Peter Finch, who died soon after the movie was released and before he could receive an Oscar for his performance, plays a network newscaster who threatens to commit suicide on the air. His character memorialized the statement: “We’re as mad as hell, and we’re not going to take this anymore.” A classic satire, Network dramatically illustrates the potential for economic decisions to undermine the nobility and even the humanity of leadership.

Norma Rae *

Release: 1979 (Twentieth Century Fox)

Director: Martin Ritt

Screenwriter: Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr.

Author of Book: Henry P. Leifermann (Crystal Lee: A Woman of Inheritance)

Cast: Sally Field, Beau Bridges, Ron Leibman

Norma Rae is the true-life story of Crystal Lee Sutton, a worker at a North Carolina textile factory who fomented the organization of a union. Sutton was fired, but the plant was ultimately organized. Of particular note was Sutton’s mute communication by means of a holding up a simple placard that stated UNION. Sally Field won an Oscar for her portrayal of Sutton. The factory’s payroll gradually shrank from 3,000 to 300, its production was offshored, and the building was demolished.

Here are some questions and prompts on Norma Rae for your reflection:

Early in the movie (at 8:30 or so), the Textile Workers Union organizer Reuben Warshawsky (Ron Leibman, portraying the real-life union organizer Eli Zivkovich) knocks on the door of the Norma Rae Wilson’s home. What is he doing that is of generalizable interest to students of leadership? Why, apart from saving money, does he want to find lodging with millworkers?

What does the hostile reaction of Norma Rae’s father, Vernon Witchard (Pat Hingle), tell you about the challenge that leaders often face? Why does he react so harshly to Reuben?

Reuben begins distributing fliers to employees outside the plant gate. Arriving for her shift, Norma Rae takes one, glances at it, and then returns to tell Reuben: “There’s too many big words in here. If I don’t understand it, they ain’t gonna understand it.” What does that remark tell you about communication as the energy — or the work, in Nitin Nohria’s phrasing — of leadership?

At about 44:15, we hear Reuben give a speech in a Baptist church to a small crowd of workers. What is compelling about that speech?

What was it that motivated Norma Rae to visit Reuben at the Cherry Valley Motel and volunteer to join his union drive?

In the scene in Reuben’s hotel room, which by now doubles as a crowded union field office, Norma Rae is working the mimeograph machine when another volunteer, Peter Gallat, shows up an hour late. Norma Rae confronts him. He explains he was at the dentist. She claims he was at a tavern. Reuben intervenes and welcomes Peter while sending Norma Rae away. A moment later, in the café where Reuben finds Norma Rae, he smoothes over the ruffled edges. What does Reuben know that Norma Rae has yet to learn?

In the movie’s climactic scene, one of the most famous in moviemaking history, Norma Rae climbs atop a table in the noisy mill and brandishes a hastily written sign that simply states UNION. She is mute. One by one, her coworkers turn off their machines. What can we, as students of leadership, learn from this scene?

The Office

(Note: Originally produced in Great Britain in 2001, The Office has been replicated in numerous countries, each with its own fictional details and cultural nuances.)

First Broadcast: 2005 to 2013 (in the United States)

Creators: Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant

Cast: Steve Carell, Will Ferrell, James Spader (all in the United States)

A hilarious “mockumentary” of day-to-day survival in contemporary business, The Office gleefully mocks the stupidity and arrogance of clueless bosses—a Dilbert cartoon as a sitcom, if you will. Anyone in management should watch every episode. Sooner or later, most of us eventually see a part of ourselves in Michael Scott, the self-centered branch manager.

Patton

Release: 1970 (Twentieth Century Fox)

Director: Franklin J. Schaffner

Screenwriters: Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North

Authors of Books: Ladislas Farago (Patton: Ordeal and Triumph) and Omar Bradley (A Soldier’s Story)

Cast: George C. Scott, Karl Malden

This eponymous movie is the story of U.S. General George S. Patton and his relationship with General Omar Bradley during World War II. Patton relies on strict discipline and demanding expectations of himself and others. However, his self-discipline does not extend to his tongue, as he is repeatedly making remarks that offend others and cause diplomatic issues.

RBG

Release: 2018 (Magnolia Pictures, Participant Media, CNN Films)

Director: Betsy West and Julie Cohen

Film Editor: Carla Gutierrez

Authors of Book: Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik (Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg)

A documentary released in 2018, RBG is a biopic of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the trailblazing litigator and, since 1993, associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and only the second woman, after Sandra Day O’Connor, to sit on the high court. (She has since been joined by Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.) RBG recounts Ginsburg’s childhood in Brooklyn, her college education at Cornell, her legal education at Harvard and Columbia, her career as a constitutional lawyer representing litigants unfairly penalized for their gender, and of course her influence on the Supreme Court for the last twenty-five years and counting.

Winning five out of the six suits that she brought to the Supreme Court as a litigator, Ginsburg played a key role in dismantling the legal apparatus of gender-based discrimination even before she ascended to the bench. On the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and then the Supreme Court, she has both charmed and challenged adversaries. This movie recounts her outside contributions to American jurisprudence, but goes beyond it to capture her iconic—and iconoclastic—personality and presence.

I especially resonated to its depiction of her long marriage, to her rock-star status among young people, to the scenes of her planking and pumping iron at the gym well into her eighties, to her self-effacing humility after she fell asleep at a State of the Union address, and to her unlikely friendship with the late conservative justice, the acerbic Antonin Scalia, with whom she shared a love of the opera. For students of leadership, this movie shows that bringing about large change is not solely the province of politicians with bullhorns or preachers with bully pulpits, and that change is commonly nonlinear and incremental. I found RBG to be immensely moving and inspiring, as well as educational, and I highly recommend it—especially to young women, who are so much in her debt.

Saving Private Ryan

Release: 1998 (DreamWorks)

Director: Steven Spielberg

Screenwriter: Robert Rodat

Cast: Tom Hanks, Matt Damon, Ted Danson, Paul Giamatti

A blockbuster that won six of the eleven Academy Awards for which it was nominated, Saving Private Ryan dramatically illustrates the impact of war on ordinary families and the potential for heroism on the part of ordinary soldiers.

Schindler’s List

Release: 1993 (Universal Pictures)

Director: Steven Spielberg

Screenwriter: Thomas Keneally and Steven Zaillian

Author of Book: Thomas Keneally (Schindler’s Ark)

Cast: Liam Neeson, Ralph Fiennes, Ben Kingsley

One of the best movies ever produced, Schindler’s List is the true story of Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who saved the lives of more than 1,000 Polish Jews in World War II by hiring them in his factories. The moral of the story is well-known, but it needs to be recalled and restated often: We are the decisions we make.

Selma *

Release: 2014 (Pathé, Harpo Films, Plan B, et al.)

Director: Ava DuVernay

Screenwriters: Paul Webb and Ava DuVernay

Cast: David Oyelowo, Tom Wilkinson, Carmen Elogo, Cuba Gooding Jr., Tim Roth, Oprah Winfrey

A historical drama, Selma recalls the three civil-rights marches from the small town of Selma to the Alabama state capital, Montgomery, fifty-four miles away, in 1965. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Ralph Abernathy, and others led the marches to dramatize their struggle for the vote. The first march ended brutally in Bloody Sunday, as police and Klansmen under the direction of Sheriff Jim Clark attacked and beat the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the Alabama River, just six blocks from the starting point. A century had already passed since the end of slavery, and yet still the South’s white majority stood in opposition; even religious leaders called for “patience,” which amounted to nothing more than silence and ambivalence in the face of rank oppression. The movie vividly depicts the fierce opposition to civil rights and the bravery of the movement’s leaders in the face of violent oppression. Although it has been criticized for oversimplifying certain aspects of history and for overdramatizing the relationship between King and President Lyndon Johnson, Selma nevertheless chronicles a historic inflection point in the American experience. Just five months later, Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Here are some questions and prompts on Selma for your reflection:

Early in the movie the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King meets with President Lyndon Johnson in the Oval Office. A moment earlier Johnson is conferring with an aide about priorities. Johnson declares that King should “get on board with what we’re doing instead of the other way around, for once.” Notice that this contest of wills illustrates tension between position-driven leadership (Johnson as president) and purpose-driven leadership (King as civil-rights advocate). These conflicts are not uncommon. How do they usually turn out? Position-based and power-based leadership often prevail in the short term, but purpose-based leadership is often more sustainable over the long term.

This movie has several examples of servant leadership. In their first Oval Office meeting, Johnson tells King: “I want to help. Tell me how.” King replies that legislation is necessary to secure voting rights. Johnson demurs. He wants King to work with the administration on the War on Poverty. So here we see an offer of servant leadership followed by what amounts to a retraction. What is King’s reaction afterward? What lessons can you derive?

In another Oval Office meeting (halfway through the film, approximately 59:00), under a painting of George Washington, Johnson tells King: “Now you listen to me. You’re an activist. I’m a politician. You’ve got one big issue. I’ve got a hundred and one. . . . I’m sick and tired of you demanding and telling me what I can and what I can’t do. You want my support on this voting thing? I need some quid pro quo from you.” What does that tell you about Johnson’s leadership?

In the second of the three marches, the white police force moves to the side of the road. The marchers are surprised, and after praying for guidance, King stands and turns back. The next day his collateral leaders are demand an explanation. King had feared an ambush. “I’d rather people be upset and hate me than be bleeding or dead,” King replies. A moment later, outside a diner, one white marcher from New England complains to another: “He betrayed trust. He called, we came, and he didn’t fulfill his own call.” Do you agree or disagree? Do you think King weakened or strengthened his leadership in that moment? Did he weaken his or strengthen his connection with his collaterals? Was this a tactical mistake for King?

Behind the overarching struggle for civil rights depicted in the film, there are two other tensions: one between Johnson and King, and another between the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Council. The latter conflict threatens to tear at the fabric of the movement. How can leaders bring people together in common cause when internal rivalries are consuming the attention and passion of people?

In yet another Oval Office confrontation, Johnson challenges Alabama Gov. George Orwell, a populist Southern Democrat who defended segregation. “I’ll be damned if I’m going to let history put me in the same place as the likes of you.” It is reminiscent of some of the floor speeches of Thaddeus Stevens that Stephen Spielberg captured in Lincoln. What can we learn from it?

How would you characterize King’s leadership, as depicted in the movie? Lyndon Johnson’s? What scenes best exemplify each man’s leadership?

Spotlight *

Release: 2016 (Participant Media)

Director: Tom McCarthy

Screenwriters: Josh Singer and Tom McCarthy

Cast: Mark Ruffalo, Michael Keaton, Rachel McAdams, Liev Schreiber, John Slattery, Stanley Tucci

Spotlight is the cinematic story of the Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation of the Boston Archdiocese’s systematic cover-up of the scandal involving rampant pedophilia by priests. Nearly two hundred fifty Roman Catholic priests and brothers were ultimately implicated in sexual abuse. The movie, which won Oscars for best picture and best original screenplay, offers numerous insights on leadership in dynamic and complex situations. It takes you inside the day-to-day work of investigative journalism and into the institutional ramparts of the Catholic church. With minor exceptions for dramatic art, its depiction of a newsroom and of the working lives of journalists is quite realistic. The grunt work behind investigative reporting is often tedious and laborious, and there can be tension between reporters and editors as to what to what will be published and when. (See also my review of Doubt, another movie that explores the tragedy of ecclesiastical sex abuse, above.)

Here are some questions and prompts on Spotlight for your reflection:

Review our definitions of leadership and management. (See the Glossary and Concepts under the Resources tab on this site for an explanation of the differences.) Does the investigative work by the Spotlight team rise to leadership? Why or why not? If so, how? If not, how could it?

Context is an important variable in leadership. What works in one situation may not work in another. What is the context of the Boston Globe’s investigation of pedophilia by priests, and why does it make the whole story remarkable?

One of the central themes of this movie is the tension between loyalty to an institution and loyalty to an ethical, moral, or legal code or norm. How does that relate to leadership?

A little over halfway through the film (approximately 1:10:45), there is a critical meeting in which Globe editor Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber) insists on a broad perspective. He explains that the story must not merely report on instances of priestly sex abuse. Rather, it has to attack the systematic cover-up that allowed priests to remain in circulation and able to commit more sex abuse. Is this an example of leadership? If so, how?

Later, roughly two-thirds of the way through the movie (approximately 1:36), investigative journalist Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo) finally gets hold of a trove of documents that had been under seal. The documents show that Cardinal Bernard Law was covering up the abuse seventeen years earlier. Rezendes is outraged. However, the Spotlight editor stalls publication of the documents. The young reporter is furious. “They knew, and they let it happen—to kids!” he screams at the editor. “Okay? It could’ve been you! It could’ve been me! It could’ve been any of us! We gotta nail these scumbags! We gotta show people that nobody can get away with it—not a priest or a cardinal or a freakin’ pope!” Then he storms out of the room. How do you think a leader—or, for that matter, a manager—should go about harnessing the positive energy of people on staff?

Good questions often lack quick and easy answers. Rather, they provoke you to think and rethink your prior assumptions and beliefs. Platitudes and bromides fall by the wayside, as they should, and you are left with the distillation of truth. What are some of the questions this movie asks but for which it does not offer canned answers?

In a scene near the end, editor-in-chief Baron consoles his staff, who had known about the severity of the problem years earlier but hadn’t gotten to the bottom of the scandal. “Sometimes it’s easy to forget that we spend most of our time stumbling around in the dark,” he tells them. “Suddenly a light gets turned on, and there’s a fair share of blame to go around.” If that is true, what does it say about the challenge of leadership in a morally obtuse world?

Stand and Deliver

Release: 1988 (Warner Bros.)

Director: Ramón Menéndez

Screenwriters: Ramón Menéndez and Tom Musca

Cast: Edward James Olnos, Estelle Harris, Mark Phelan

This is the mostly-true story of Jaime Escalante, an engineer who becomes a high-school math teacher in a tough East Los Angeles neighborhood. After several years of increasing success, he decides to teach calculus, which requires the students to attend additional classes during the summer and on Saturdays. Despite insinuations of cheating, several of the students score well on the Advanced Placement exam. The movie has powerful lessons for leaders on the importance of elevating expectations and then providing steadfast support to help people meet the high expectations.

Twelve O’Clock High

Release: 1949 (Twentieth Century Fox)

Director: Henry King

Screenwriters: Sy Bartlett and Beirne Lay Jr.

Cast: Gregory Peck, Hugh Marlowe, Gary Merrill

I first saw this movie in a graduate-school seminar on leadership. The tacit endorsement of rigid hierarchy and leadership by command and control bothered me then and, twenty-five years later, bothers me more now. Still, Twelve O’Clock High is an outstanding story of a leader who confronts pervasively poor morale, who courageously leads from the front, and who uses early successes to build camaraderie and confidence.

We Are Marshall

Production: 2006 (Warner Bros.)

Director: McG

Screenwriter: Jamie Linden

Cast: Matthew McConaughey, Matthew Fox

This inspiring film has one of the all-time best pre-game pep talks by any coach anywhere. After referring to the university’s tragic past, coach Jack Lengyel (Matthew McConaughey) turns the subject to the afternoon’s game and the bigger, faster, stronger opponent Marshall faces. “They know it too. But I want to tell you something that they don’t know. They don’t know your heart. I do. I’ve seen it. You have shown it to me. . . . When you take that field today, you’ve got to lay that heart on the line, men. From the souls of your feet, with every ounce of blood you’ve got in your body, lay it on the line until the final whistle blows. And if you do that, if you do that, we cannot lose.”

The West Wing

First Broadcast: 1999 (Warner Bros. Television)

Scriptwriter: Aaron Sorkin

Cast: Martin Sheen, John Spencer, Stockard Channing, Rob Lowe, Allison Janney

Deserving winner of just about every award a television drama can earn, The West Wing looks at the full panoply of challenges that confront every U.S. president, as well as leaders in other situations: finding purpose, creating strategic focus, persuading the reluctant, addressing divergent interests, balancing multiple stakeholders, and much more.

The Wizard of Oz

Production: 1939 (MGM)

Director: Victor Fleming and George Cukor

Screenwriters: Noel Langley and Florence Ryerson

Author of Book: L. Frank Baum (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz)

Cast: Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Jack Haley

A beloved children’s story as a movie with lessons for leadership? Absolutely! Think of the scarecrow as the need for curiosity in the workplace, the tin man as the need for passion, and the lion as the need for courage. The yellow brick road? It’s the journey they walk together. Kansas? The destination. It all fits.

Enjoy!